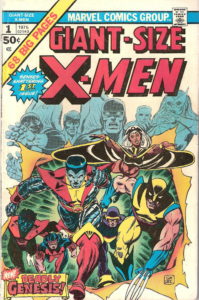

In 1974, a suggestion was made by then-Marvel President Al Landau to introduce an international team of super-heroes that could then be sold in various countries. Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief at the time, Roy Thomas, felt this request could serve as an excellent means of reviving the X-Men, and assigned writer Len Wein and artist Dave Cockrum to create the “all-new, all-different” international X-Men. Of course, by the time the book was published, the “international publishing” directive had been abandoned, and many of the characters came from countries that would never have been a viable publishing market for Marvel, but who cared? The X-Men were back and stronger creatively than ever. In GIANT-SIZE X-MEN #1, published May 1975, writer Len Wein and artist Dave Cockrum introduced comics fans to seven new X-Men. Aside from the returning Professor Xavier and Cyclops, there was the Russian Colossus, the Canadian Wolverine, the German Nightcrawler, the Japanese Sunfire, the Irish Banshee, the African Storm and the Native American Thunderbird.

The series resumed publication where the last had left off, with number 94. After only two issues, Wein left the series when he was promoted to Editor-in-Chief, turning over the scripting to newcomer Chris Claremont, who would go on to write the series for 16 years, an astounding achievement in comics. It was in Claremont’s hands that the series really coalesced into what most people think of when you say “X-Men”: subplotting that would carry storylines through years of advancement, an ever-shifting and evolving cast of characters, a willingness to tell big stories and break many of the conventions of Marvel’s comics up to that point (such as killing off main characters, or portraying heroes who weren’t always entirely heroic), and most important, an emphasis on character. Sure, what the X-Men did made them interesting to read about, but it was who they were that kept you coming back.

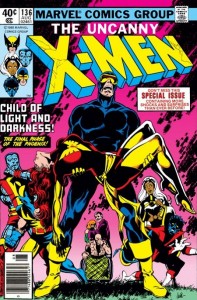

If Chris Claremont gave the X-Men their heart, then without a doubt it was the team of Claremont and artist John Byrne that gave the series what it had always lacked: star quality. By 1979, UNCANNY X-MEN was really starting to pick up steam as one of Marvel’s most popular series. Under the stewardship of Claremont and Byrne, along with steady support from inker Terry Austin and letterer Tom Orzechowski, UNCANNY X-MEN was combining tense, action-packed drama with Claremont’s keen characterization, illustrated with heart and flair by Byrne, who was providing some of the best art of his career. The Claremont-Byrne team hit its zenith with issues #129 to #138, nowadays more commonly known as “The Dark Phoenix Saga.”

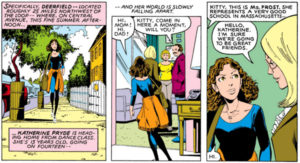

There’s a lot going on in these issues. New characters are introduced, particularly Kitty Pryde, the new “kid sister” for the team who would go on to become one of Marvel’s most enduring and popular female characters. Wolverine is brought even more to the forefront as the X-Men’s lethal loose cannon, and most significant, the team is changed forever as Jean Grey finds herself unable to control her ever-growing power as the Phoenix, and elects to commit suicide instead before the horrified eyes of her lover Scott Summers.

This was heavy stuff, and a breakthrough story in a lot of ways for Marvel. Aside from its mature handling of such issues as Scott and Jean’s romance and Wolverine’s lethal tendencies, there hadn’t really been a series that killed off one of its main characters permanently (at least it was expected to be permanent, and was treated as such for a decade or so), and this monumental, now-classic turn of events almost didn’t happen. As the story goes, the creators’ original intention was never to kill Jean off, but instead to psychically neuter her, rendering her completely powerless. However, when penciller Byrne drew the sequence of Phoenix consuming the star, he included the scenes of the planet of the “asparagus people,” as he later called them, being destroyed in the process. When then-Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter saw this, he insisted that the character be killed off as a consequence of her actions, as he refused to publish a series featuring a genocidal mass-murderer as a hero. Under heavy editorial pressure from above, Claremont and Byrne reluctantly altered the finale of their story, with its new ending of a remorseful Jean committing suicide to save the planet from herself.

The Scott Summers-Jean Grey romance hit a climax here that it never quite reached again, even after Jean was resurrected and the characters were married in the mid-1990s. Claremont does a remarkable job at bringing Scott’s emotions to the forefront here (primarily through his concern for Jean’s welfare), and the few moments of peace and happiness Scott and Jean manage to claim for themselves seem all the sweeter due to Scott’s near-constant worry over Jean’s rapidly developing powers. It’s a tough thing to really sell a romance as believable on the comic-book page; between Claremont’s words and Byrne’s renderings, they manage to more than pull it off, making Scott’s grief all the more palpable.

There’s a lot here to admire besides the Jean Grey storyline. The introduction of Kitty Pryde, while helping to fill the void that was about to be created with the loss of Jean, also helped reconnect the book with its original school-based concept, injecting a much-needed dose of youth and vitality into a school paradoxically almost entirely populated by adults. As for Kitty herself, thanks to Claremont’s charming characterization and Byrne’s appealing design, Miss Pryde would become one of the series’ most popular characters, and remain a mainstay of the book for the next 15 years or so.

While not yet remotely the breakout star of the book he would eventually become, Wolverine really comes into the forefront for the first time here, exhibiting more and more of the lethal ferocity that the character would eventually be famous for. The introduction of the Hellfire Club also added a steady stream of new stories and adversaries to the title, while the suggestive S&M-influenced attire on Emma Frost and the Black Queen added a hint of sexiness to the series without crossing the line to something inappropriate for an all-ages book.

While Claremont would stay on the series for another decade (Byrne had left only a few months after the end of the Phoenix story) and contribute many excellent stories and characters to the ever-growing X-Universe, it’s still “The Dark Phoenix Saga” that remains the crown jewel in the X-Men library.

Claremont can thank The Avengers for the Hellfire Club and the elements it brought. Not the Earth’s Mightiest Heroes, but John Steed and Emma Peel. The inspiration for Emma Frost and the Hellfire Club came from the episode “Brimstone,” which featured a revived Hellfire Club. Emma Frost gains her name from Emma Peel, plus the inspiration for the outfit (though Diana Rigg’s black outfit was more direfctly translated as Jean’s attire, as the Black Queen) and guest star Peter Wyngarde would provide the name and look for Mastermind, as Jason Wyngarde (Wyngarde was famous as the character Jason King). Hellfire Club member Sebastian Shaw was based on Richard Burton, Harry Leland on Orson Wells (who was Harry Lime in the Third Man and had a Jed Leland in Citizen Kane), and Donald Pierce on Donald Sutherland (who played Hawkeye Pierce in the MASH movie).