Time for a “Back-in-my-day” moment: when I was first reading comics as a kid, there were certain characters that I only heard about and fleetingly saw, since reprints were scarce, back issues weren’t readily available (this was before comic shops, mind you), and the notion of the Internet was about as realistic as the computer on the Starship Enterprise. Therefore, only the characters that were appearing at the comics rack down at the pharmacy were “real,” and everyone else I heard about fell into that gray area, where I knew they existed, had heard about them from my dad or references in other books, but they otherwise remained a total mystery. In that category were folks like Bucky Barnes, Airboy, and the subject of today’s discussion, Plastic Man.

In my six-year-old mind, there were only two real stretchy guys: Reed “Mr. Fantastic” Richards and Ralph “the Elongated Man” Dibny. Even the name didn’t make any sense: Plastic Man? Toys were made of plastic, and plastic was hard.

Eventually, I began to get more exposure to Plas, first through his very occasional appearances in DC Comics (we’ll get to why they were occasional in a little bit), and later through his ABC Saturday-morning cartoon series, which started off as merely bad and ended as just plain awful. In time I’d come to recognize and admire the character for all its innovations and strengths (none of which were apparent in his 1970s appearances, TV, comics or otherwise), even if for me, he’ll always be a second fiddle to Ralph Dibny. But let’s handle things the right way, from the beginning, which takes us all the way back to 1941.

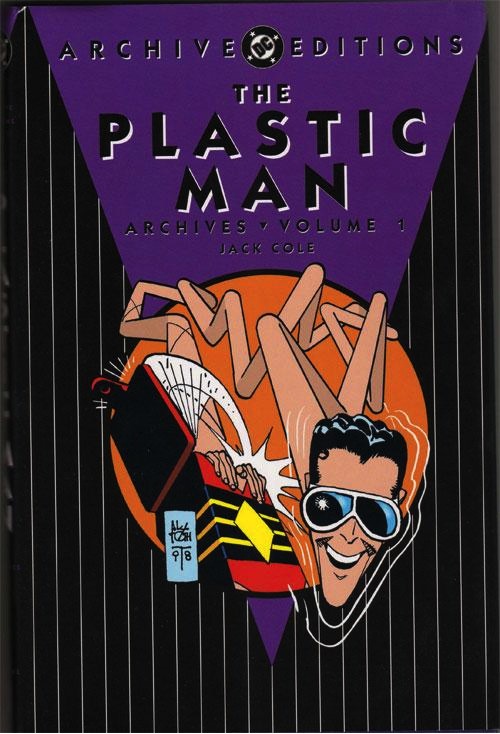

As we’ve discussed many times in the past, the comics industry in the late 30s and early 1940s was a booming business, and while National Comics/All-American may have been the industry leader with their triple threat of Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman (as well as a more-than-formidable second string in Flash, Green Lantern and Hawkman), there was plenty of room for rival publishers to make a name for themselves. Fawcett was making quite a splash with Captain Marvel, Bulletman and Spy Smasher, Timely had Captain America and the Human Torch, Hillman had Airboy and the Airfighters, and so on. Seeing the success of this new venture, printer Everett “Busy” Arnold began his own comic-book publishing company, entitled “Quality Comics.” Along with Quality, Arnold was also involved in a separate business venture, a partnership with Will Eisner in Eisner’s newspaper-circulated comic book THE SPIRIT. With World War II on the horizon, Arnold feared that his young partner Eisner would soon be drafted, and leave him without an artist on their new project. Looking to protect his interests, Arnold decided to hire another artist to create another detective-type comic, with the idea being to groom him to replace Eisner, should worse come to worst. (Eisner tells the story himself in the foreword to DC’s first PLASTIC MAN ARCHIVES volume, by the way.) Arnold’s choice? A young artist from New Castle, Pennsylvania named Jack Cole.

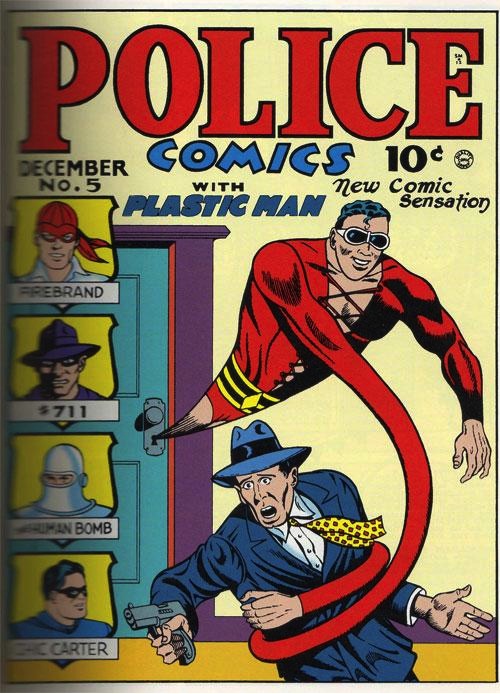

Jack Cole had broken into the business in 1937, working for Harry Chesler’s studio on such forgettable features as “TNT Todd of the FBI” and “Peewee Throttle.” Cole would take a position as an editor at Lev Gleason Publications in 1939 working on SILVER STREAK COMICS, where he worked on that company’s most notable creation, the original Daredevil. Cole also spent some time at MLJ Comics (later much better known as Archie Comics), where he worked on such characters as the Comet (a Cole creation) and the Hangman. Cole was hired away by Busy Arnold in 1940, and indeed, one of the first things he did was Arnold’s requested knockoff of the Spirit, a near-identical fedora-and-domino-mask wearing sleuth called Midnight. Although Midnight wasn’t without its charms (particularly his sidekick, a talking monkey, which is always funny), it was with a backup character in Quality’s new POLICE COMICS #1 (August 1940) that Jack Cole made his real mark, a character so little anticipated that he barely made it on the cover, relegated to a head-shot on the left-side margin alongside fellow also-rans the Human Bomb, Phantom Lady and the hilariously named vigilante (about whom I’m dying to know more) The Mouthpiece, while the ostensible star of the series, The Firebrand, garners the majority of the cover, bludgeoning what looks like a German artilleryman with a monkey wrench.

In fact, Plastic Man’s six-page debut was pushed all the way to the back of POLICE COMICS #1, a position it wouldn’t remain in for long.

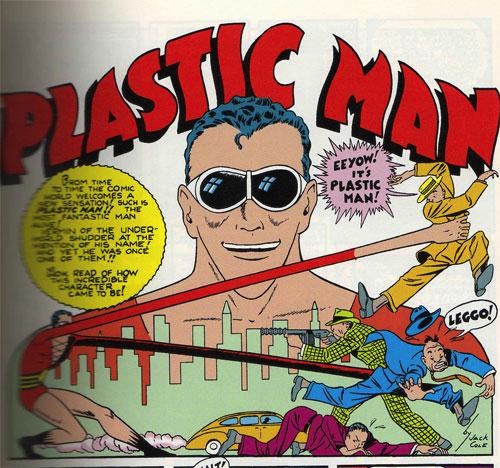

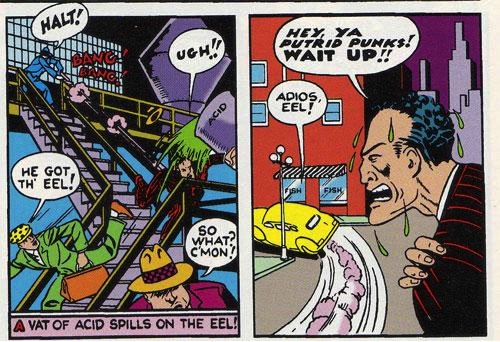

Plastic Man’s story begins with a break-in at the Crawford Chemical Works, where career criminal Eel O’Brian and his gang are making off with $100,000 in cash. Apparently, the chemical biz was where the money was at in 1940. Before they can make a clean getaway, they’re caught by the plant’s security guard, who opens fire, shooting Eel twice. As Eel falls, he knocks over a vat of acid, which spills over him, seeping into his open wounds from the gunshots.

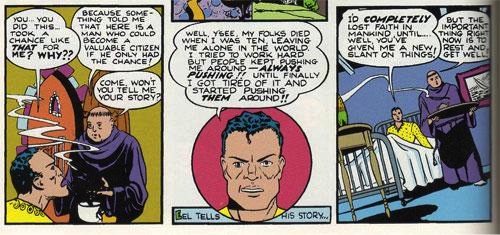

Terribly injured and burning from the acid in his wounds, Eel still manages to make his escape from the city, running through swamps and forests until he’s discovered by a kindly friar and taken to Rest-Haven, where he’s hidden from the police and nursed back to health by the friar, who senses a great capacity for good in Eel O’Brian. When asked why he’d taken to a life of crime, Eel tells his story:

Given a renewed faith in mankind by the friar’s belief in him, Eel begins to reconsider his life, even before making a startling discovery:

Somehow, the acid had gotten into his bloodstream and created some sort of physical reaction, rendering his body completely rubbery and stretchable. Energized by his spiritual epiphany and his newfound abilities, Eel O’Brian thanks the friar and makes his return to the city, determined to use his new powers against crime, starting with “the rats who deserted [him] on that Crawford job.” Sure, he’s turned over a new leaf, but he’s still human.

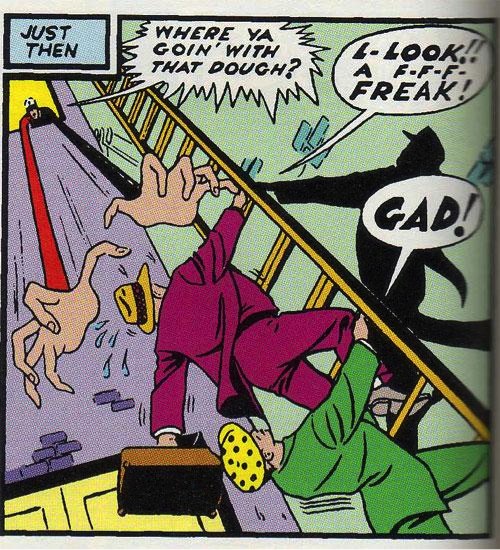

Eel returns to the gang’s hideout and demands his cut of the loot, and is brought in on their next job, a bank messenger robbery, this time with Eel at the wheel. While Eel “waits in the car,” the thugs head to the elevator, where they rob the messenger and disable the elevator, climbing up the emergency ladder to the next floor. That is, until they’re met with an unexpected, freakish sight:

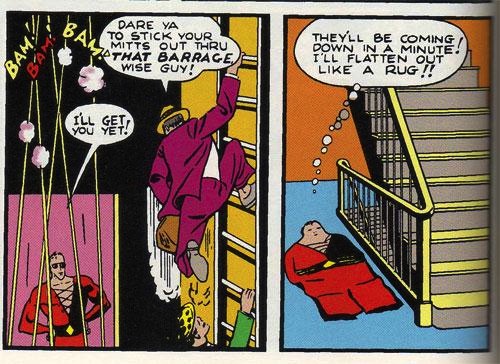

Clearly, Plastic Man doesn’t yet realize how bulletproof he is, because the barrage of gunfire laid down by the startled thugs makes him change his plan of attack. Instead he poses as a rug, and surprises them when they come down the stairs, the first in a long line of inattentive criminals not to notice that ordinary objects that happen to be bright red and yellow just might be bad news.

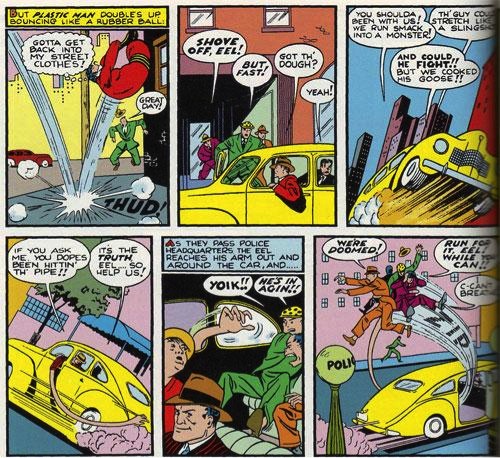

Plastic Man chases the remaining crooks to the roof, where one of them gets the drop on him, shoving him off the side of the building. Plastic Man bounces to safety, and returns to the getaway car to assume his role as Eel. The gangsters pile in the car and tell Eel all about their encounter with the mysterious rubber man, until Eel stretches his arm out his window when the car passes Police Headquarters, reaches around the back of the car and pulls the crooks out, depositing them in the middle of the station house.

In the very next issue, Plastic Man wrangles a position with the police department after closing down a powerful dope racket and bringing in a wanted criminal, namely himself, Eel O’Brian (Although Eel manages to give the cops the slip after Plastic Man “leads them right to him,” so Plastic Man still gets credit for the bust.) This closely followed the model of Eisner’s Spirit, with Plastic Man working very closely with the police, even taking direct orders from them, as opposed to the more loose affiliation readers saw in books like SUPERMAN and BATMAN.

It didn’t take long for Quality to suss out who the real star of their new series was. After only four months, the cover of POLICE COMICS #5 (December 1940) tells the tale, with Plastic Man clearly getting the star treatment, as well as an increased page count, with the Plastic Man stories now in the lead position, coming in at a much roomier thirteen pages.

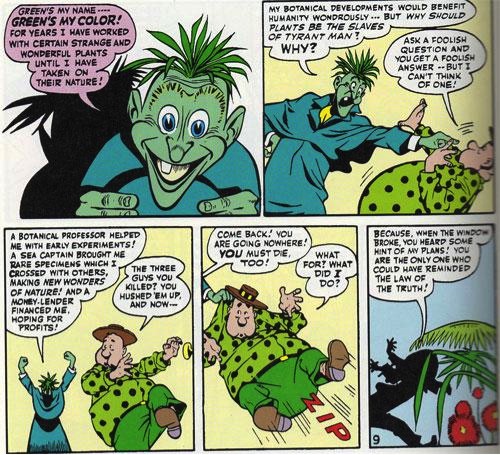

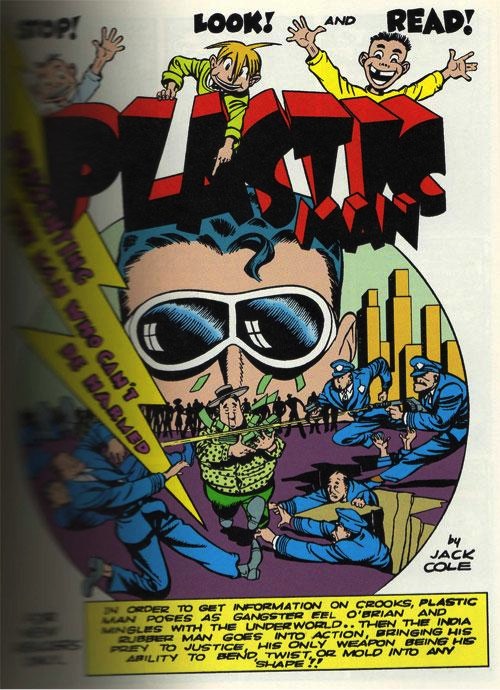

Take a look at how much Cole’s work had advanced only a year after Plastic Man’s debut, with the introduction of Plas’s longtime sidekick Woozy Winks in POLICE COMICS #13, in “The Man Who Can’t Be Harmed.”

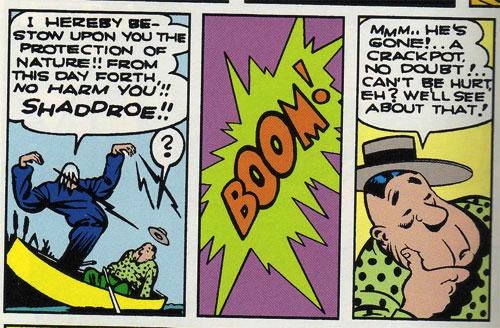

As you can see, Cole had already began to transition to a much broader, cartoonier style, which gave him much more flexibility (no pun intended) when working with a character like Plastic Man who can literally become anything. In the story, ne’er-do-well Woozy Winks absentmindedly saves the life of a soothsayer, who bestows upon Woozy the protection of nature, making him completely impervious to harm.

Flipping a coin to determine how to use his new gift, Woozy embarks on a citywide crime wave, which Plas is helpless to stop, thanks to the forces of nature preventing any harm from befalling Woozy.

Finally, Plastic Man resorts to psychology to defeat Woozy, bringing him down with nothing more than a good old-fashioned guilt trip.

Plastic Man and Woozy would have many an adventure over the next 16 years. Next week, we’ll look at a couple of my favorites, as well as bring ol’ Plas up to the more-or-less present day.

Comments are closed.