DC Comics’ Elseworlds stories have typically been presented as one-shots or miniseries outside a comic book’s main continuity and issue numbering. Thanks to the Elseworlds concept, Batman fans have been treated to seeing the Dark Knight portrayed as a reverend (Batman: Holy Terror), a vampire (Batman & Dracula: Red Rain), and a rampant psychotic (Catwoman: Guardian of Gotham), as well as meeting Jack the Ripper (Batman: Gotham by Gaslight), Lord Greystoke (Batman/Tarzan: Claws of the Cat-woman), Edgar Allan Poe (Batman: Nevermore), and others. Wonder Woman, Superman, the Justice League, and Green Lantern have had their fair share of alternate-reality stories as well—again, typically outside their respective monthly titles. And, of course, other publishers have also gotten into the imaginary-reality game.

When writer Mark Millar neared the end of his tenure on the second Swamp Thing series in 1996, he created a rather unique Elseworlds tale for that long-running title. Millar’s Swamp Thing saga was unique in the character’s history, as it introduced a slew of radical new concepts to the mythos that rocked its very foundation. Naturally, his take on telling Elseworlds tales was no less unique.

Swamp Thing has long marched to the tune of its own muck-encrusted mockery of a drum, ever since Alan Moore famously turned the series’ premise (that scientist Alec Holland had been transformed into a bog beast and thereafter strove to restore his lost humanity) on its end. Moore revealed that the creature not only would never be cured, but had never been Alec Holland to begin with, and was actually a plant elemental from a lineage of similar beings going back billions of years. So it should come as no surprise that when Millar presented a Swamp Thing Elseworlds tale in issue #165, he did so not as a standalone story, but within the pages of the monthly comic—and without letting on, until the end of the issue, that it even was an Elseworlds story.

The issue focused on Chester Williams, a character Moore had introduced in issue #43 (“Windfall”), the seventh chapter of his fourteen-part “An American Gothic” saga. Chester—based on artist Stephen R. Bissette’s college roommate, Larry Loc—was a peace-loving environmentalist with bright red hair and a fondness for the hippie lifestyle and aesthetic, who ultimately became a college professor in order to help guide young minds. Gentle and caring, Chester was easily the nicest person to appear in the history of the title, and quickly became a fan favorite due to the concern he showed for everyone he knew, and for the planet as a whole. He was the heart of the comic, serving as not only a vehicle to voice the various writers’ concerns, but also as a confidante and best friend to Swamp Thing and his wife, Abby Arcane-Cable-Holland.

When Chester fell in love with Liz Tremayne, readers smiled at seeing him happy. When she left him for another woman, fans shared his heartbreak. When the Parliament of Trees tried to kill Chester to make him Earth’s next plant elemental, readers were on the edge of their seats with worried excitement. And when he narrowly avoided that fate, they released a collective sigh of relief. Alec and Abby may have been the main players, but for many fans, Chester was the favorite of the lineup. He was a guy anyone would be lucky to have as a friend, and the last person one could imagine harming another soul. No matter how bad things got for Alec and his companions, Chester never ceased to be the optimistic, idealistic, forward-thinking hippie fans had come to love.

Until Mark Millar came along, that is. Then all bets were off.

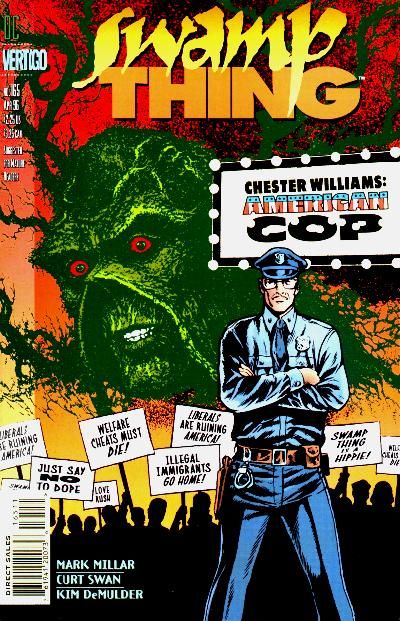

Issue #165, titled “Chester Williams: American Cop,” sported a profoundly uncharacteristic cover image of Chester proudly standing alongside protestors waving signs proclaiming “Just Say No to Dope” and “Illegal Immigrants Go Home!” and “Liberals Are Ruining America” and “Swamp Thing Is a Hippie!” Illustrated by Curt Swan and Kim DeMulder, the issue was released in March 1996 but bore an April cover date. Eagle-eyed readers might have noticed the significance of that fact, as the story would prove to be an entertaining and amusing (not to mention horrifyingly prescient) April Fool’s Day joke on the loyal readership.

The issue opened with Chester hosting a raucous party attended by sexually titillated, narcotics-enhanced teens and their lust-filled professors. When the students thanked him for showing them that knowledge is bad and getting stoned is good (an early hint that something was up, since Chester genuinely cared about educating the minds of young people and would certainly not have condoned teachers sexually exploiting their teenaged students), he decided it was time to grow up. He summarily called the police, arranged for everyone at the party to be arrested, and expressed not only regret at his hippie lifestyle, but also extreme patriotism and a desire to be a cop himself.

If this behavior didn’t raise eyebrows, what happened next surely did: Chester proceeded to denounce liberalism, pacifism, drug use, and acceptance of homosexuality. Readers’ jaws dropped in amusement and (for anyone who didn’t see through Millar’s prank) outrage as kind, gentle, left-wing Chester embraced the “New Right” by becoming a radically conservative Republican and extolling the virtues of guns, anti-feminism, police brutality, and beer-guzzling with the guys each night—always with over-the-top dialogue that just made the narrative even more shocking and bizarre to behold.

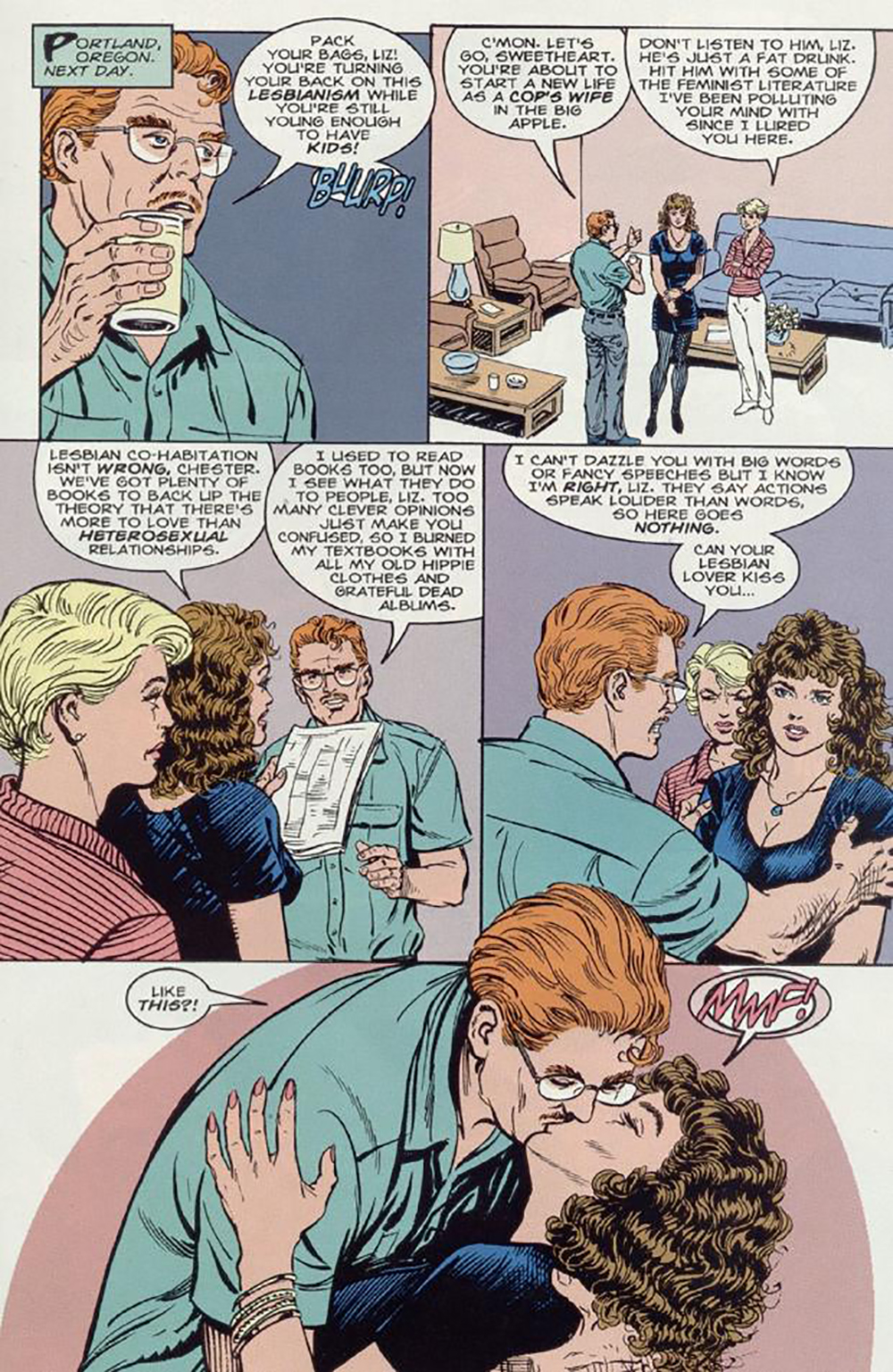

The situation became more absurd when Chester decided that losing Liz to another woman didn’t sit right with him. To that end, he visited her in Portland and wooed her away from her lover Barb, simply by grabbing her and giving her a big, strong, manly kiss that, of course, made her straight once more—and even made Barb decide to try heterosexuality, too. Liz and Chester got married, but instead of celebrating their honeymoon, he set her straight on their wedding night with a slap to the face as he left her alone for the evening, saying he was against all forms of sex—even post-marital! (Though he did express a desire to be naked with Pamela Anderson.)

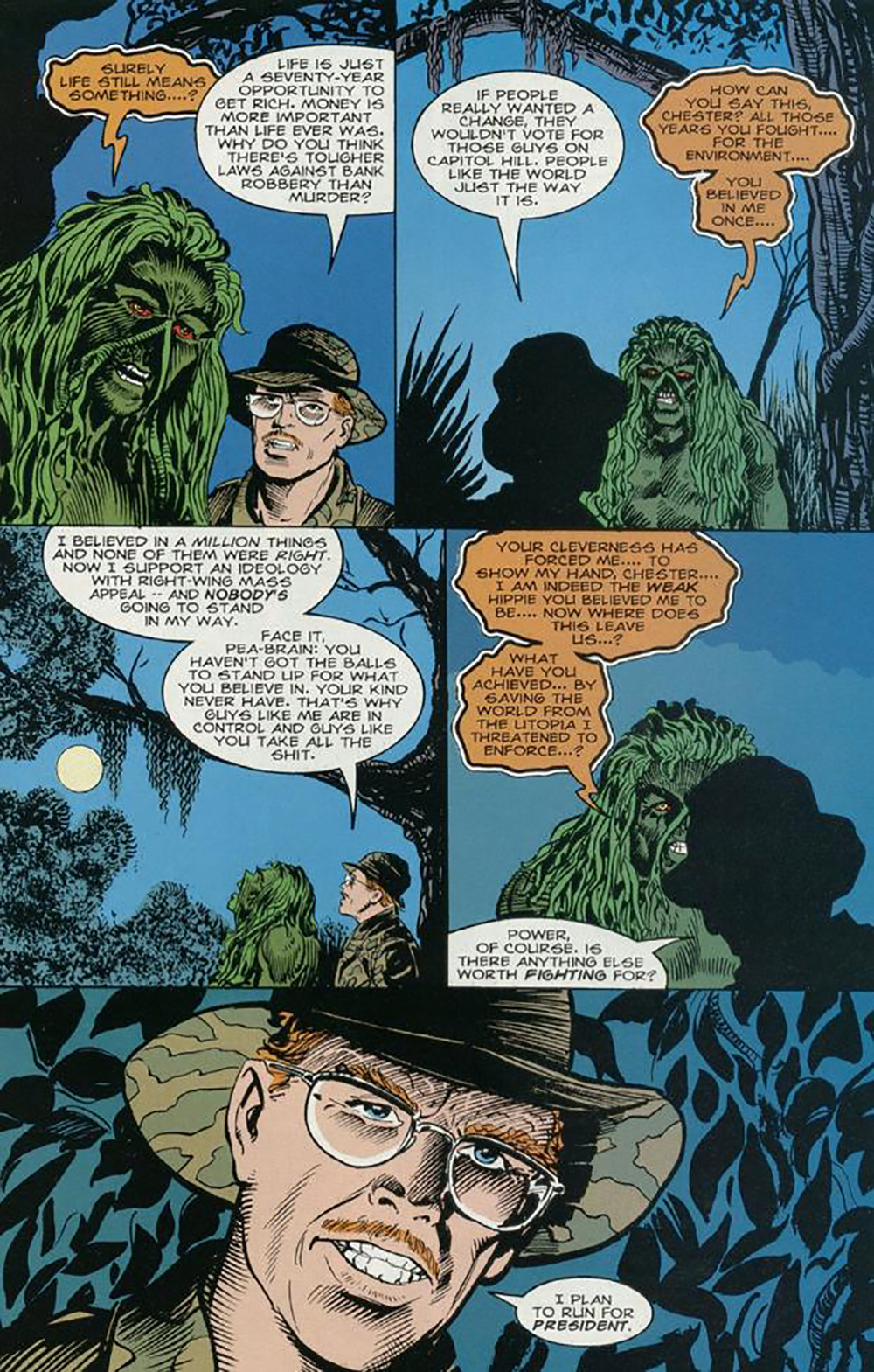

After Chester saved Chelsea Clinton’s life during a hostage standoff, he accepted a lunch invitation to the White House (despite his newfound distaste for Bill Clinton’s stance on gays in the military). The President asked him to help alleviate a crisis involving his one-time friend Swamp Thing, who had issued the world’s leaders an ultimatum: get serious about environmental reform or face his wrath. Taking time out from a lecture tour on the threat of anal copulation, Chester traveled to the bayou, where he scolded Alec about how big business is the backbone of America, and why the bog god should accept that and stop pushing his bleeding-heart liberal agenda.

Convinced immediately, of course, by Chester’s conservative, non-hippie cleverness, Swamp Thing abandoned his plan to spread utopia around the planet and instead retreated back to the swamp, content with letting huge corporations run everyone’s lives and exploit the environment. Chester then ran for President and won the election, enabling him to spread his anti-immigration stance, white supremacy, homophobia, fascism, and corporate shilling to tomorrow’s youth.

If you’ve ever read an issue of Swamp Thing featuring the lovable, dope-smoking redhead, you will do doubt recognize how patently absurd every single aspect of “Chester Williams: American Cop” truly was. Not one thing Chester said or did in any way matched what fans had come to expect from the character after a decade of enjoying his status as Swamp Thing’s analog to Superman’s pal Jimmy Olsen.

Gone was the hopeful, helpful, hate-free hippie. In his place was a violent, fanatical, xenophobic, hypocritical, stereotypically right-wing extremist—a prototype of the modern-day alt-right movement. It was the very antithesis of what Chester Williams stood for, and it was both hilarious and disturbing to see him portrayed in this manner. It was like reading a story called “Martin Luther King Jr.: White Supremacist” or “Woody Allen: Nazi Warrior” or “Vlad the Impaler: Grief Counselor.”

You may be thinking, “OK, this sounds funny, but how could anyone not have realized this was an Elseworlds April Fool’s joke?” Well, consider the Halloween 1938 radio broadcast of War of the Worlds, which panicked listeners who thought Earth was being invaded by Mars, despite it clearly being a play based on a popular novel. If people could believe Earth was being invaded by Mars—which, incidentally, meant accepting that reporters covering the attack could somehow travel across the United States within minutes, from one scene to the next—then it’s not so difficult to believe that some might have missed the obvious satire of Chester’s 180-degree transformation. Thankfully, by the time readers reached the letters page, editor Stuart Moore made sure to let them in on the joke, just in case some didn’t quite get it, by announcing the following:

“VERY SPECIAL NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: Just wanted to tell all you readers I’m sorry about this issue; Mark got carried away and, well, you know how he is. The whole thing is an imaginary story—I mean, an Elseworlds—anyway, it didn’t happen. Anywhere. Chester will just wake up tomorrow from a bad trip or something, and that’s that.”

Whew! It was all just a bad trip, man.

DC’s list of Elseworlds stories is vast and varied, and anyone collecting and reading them all can find much to enjoy. Those who overlook Swamp Thing #165 would miss out on one of the more entertaining, albeit more ridiculous, “What if…?” stories out there. “Chester Williams: American Cop” is a great read because it’s so unexpected—though sadly, it’s not quite so funny as it once was, now that alt-Chester’s bigoted, fascist attitudes have begun to take hold on the nation, and on the world at large.

In 1996, Chester’s imaginary America was a humorously absurd Elseworld; these days, it’s scarily recognizable reality. If only Stuart Moore would announce that the past couple of years have all been a practical joke perpetrated by Mark Millar.

Comments are closed.