With this week marking its 25th anniversary, let’s take a look back at the standout Batman animated offering from Warner Brothers, the superlative 1992 classic BATMAN: THE ANIMATED SERIES.

Before ’92, action-adventure animation was all but dead on American television. Following the success of its new comedy series TINY TOON ADVENTURES, Warner Animation President Jean MacCurdy made it known that they were looking to develop a new BATMAN animated series, and that anyone with an idea was welcome to make a pitch. TINY TOONS storyboard artist Bruce Timm and background painter Eric Radomski were chosen to put together a sample reel, and their two-minute short netted them the jobs as the producers of the new series. After some initial problems with the series’ first story editor, who clearly had a different, more juvenile take on what the series should be (which are glaringly obvious in several of the earliest episodes, including “The Underdwellers,” in which Batman saves a band of homeless tykes from an underground slavedriver called “the Sewer King” and “I’ve Got Batman in My Basement,” which is pretty much exactly what it sounds like, about a little boy who hides a poisoned Batman from the Penguin) writers Alan Burnett and Paul Dini were brought in to spearhead the scripting of the series. Burnett and Dini shared Timm’s vision of how the character should be portrayed: dark, serious and brooding.

The intentions for this new BATMAN series were made very clear in the series’ pilot , “On Leather Wings,” written by Mitch Brian and directed by Kevin Altieri, who would go on to direct many of the series’ best episodes. This was a Batman unlike any that had been previously seen in TV animation. Batman was at odds with the police, although he clearly had a tenuous alliance with Commissioner Gordon. Batman was good with his fists, but also displays some actual detective work in investigating a series of break-ins at Gotham pharmaceutical companies. Appearing briefly was Gotham District Attorney Harvey Dent (who would eventually become the tragic villain Two-Face), indicating that the series would in fact be developing its characters over time. Finally, when the true culprit is revealed as Dr. Kirk Langstrom, who has turned himself into the Man-Bat, Batman and the half-bat, half-human creature have a lengthy, knock-down, drag-out fight sequence that lasts through most of the third act, and was probably the most violent fight scene ever intended for TV animation at the time (it wouldn’t be for long, though).

There’s a moment when Batman is riding on Man-Bat’s shoulders and is just wailing on him with repeated punches to the head, where, when first watching it in a sneak preview at Wonder-Con in Oakland, I remember sitting back in my chair and thinking “They’re really going to show this on television?”

Even the consequences of violence were shown, as a bloodied and battered Batman is seen at the end of his tussle with the Man-Bat.

(I remember Bruce Timm remarking after the episode was shown, “That’s all the blood Fox is letting us have for the season.”)

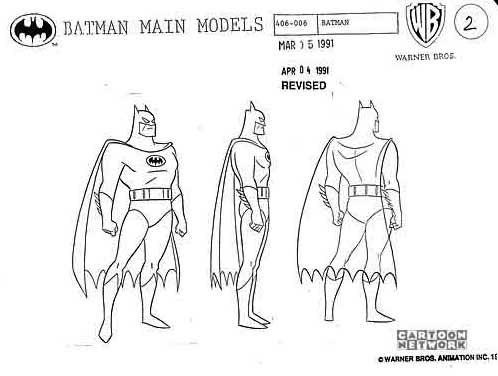

But it wasn’t just the stories that were groundbreaking. The character design, primarily the work of Bruce Timm, along with artists Lynne Naylor, Kevin Nowlan and Mike Mignola, among others, eschewed the detail-heavy, ultra-real style favored by adventure cartoons in the past, in favor of a cartoonier approach, for lack of a better word, which combined the barrel chests and square jaws of the Fleischer SUPERMAN cartoons of the 1940s with the clean linework of Alex Toth (the influence of whose Space Ghost design is clearly apparent). The influence of such Batman artists as Kane, Sprang, Miller and Mazzuchelli is also in evidence.

Furthermore, the entire series was given a moody, timeless feel, in which 1940s architecture, wardrobe and roadsters co-existed with modern-day, late ’90s technology, making the series feel instantly nostalgic yet never dated. The backgrounds, designed by Ted Blackman based on Eric Radomski’s vision, were painted on black paper, lending the entire series a noir-ish darkness appropriate to their vision of the Dark Knight.

The acting on the series was top-drawer as well. Rather than go to the same recycled group of cartoon voice actors who had been working in every Saturday-morning series at the time, series voice director Andrea Romano opened the auditions up to the best actors available, and instructed them that the show was to be played straight, as if they were performing a film or stage role. In addition, as frequently as possible, the actors would record their roles together, providing an interplay and energy not possible when parts are recorded piecemeal. As a result, the casting for BATMAN: THE ANIMATED SERIES resulted in what I believe to be the most talented cast ever assembled for an animated series, with actors who in many cases could have easily stepped into the part in a live-action feature-film version, and performed splendidly. In addition, the score for the series was provided by Shirley Walker and her team of composers, whose lush, operatic soundtracks granted each episode a soaring, larger-than-life feel.

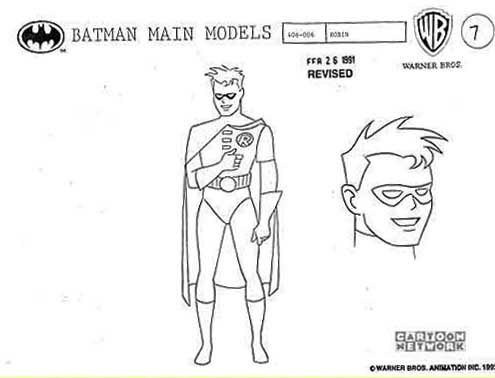

The series, at least in its first incarnation, focused primarily on Batman, with an 18-year-old Robin (attending college upstate as Dick Grayson) appearing infrequently and in a supporting role. The Robin design combined the Dick Grayson character with the current costume worn by the comic books’ third Robin, Tim Drake.

Probably the best Robin appearances in the first series (First series? Yep. Eighty-five episodes were produced for the FOX network before the series was slightly re-designed and relaunched for the WB, with 27 new episodes airing with their new Superman series as “The New Batman/Superman Adventures”) came in the two-part episode “Robin’s Reckoning,” written by Randy Rogel and directed by Dick Sebast, which showed via flashback the tale of the murder of Dick Grayson’s parents and his adoption by Bruce Wayne, told in counterpoint to Robin’s long-awaited revenge on the man who killed his mother and father.

Notable Robin moments in the first series were pretty scarce, although the character does provide one of my favorite one-liners in the whole series, in the episode “Lock-Up,” written by Paul Dini, in which Robin quips in an announcer-style voice, after a Bruce Wayne-funded prison initiative results in a crazed warden turned supervillain, “Another fine villain, brought to you through a grant from the Wayne Foundation!” Heh.

As for Batman, Kevin Conroy gave a nuanced, textured performance, in which he managed to wring the most intimidation, anger or pathos out of as few lines as possible. Conroy also managed to deftly delineate between Batman, Bruce Wayne and Bruce Wayne’s public persona, altering his voice’s pitch and timbre to make them each instantly identifiable, yet still recognizably the same character at its core.

The Batman design made use of the classic blue and gray Silver Age costume, with the yellow oval chest emblem and a refined version of the cylinder-pouch utility belt.

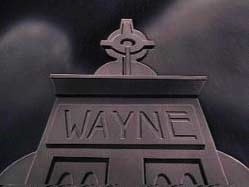

While the series wisely never bothered to do an “origin” episode, considering the character’s genesis to be fairly common knowledge by this time, they didn’t skirt around the death of Bruce Wayne’s parents and how it tortured him and forced him into his life as the Batman.

For example, in the episode “Two-Face, Part Two,” a nightmare Bruce is having in which he is tortured by his guilt in allowing his close friend Harvey Dent to become Two-Face shifts dramatically to an older, even more keenly felt agony. In the dream, Two-Face falls from a collapsing footbridge, screaming at Batman, “Why didn’t you save me?” Batman runs to the edge and peers down into the abyss, and is met with the sight of his parents, alone under a street lamp at the site of their murder, looking up at Bruce and asking “Why didn’t you save us?” Brrr.

The other constants in the series besides Batman and the occasional Robin appearance were Efram Zimbalist Jr.’s Alfred, providing the requisite amount of dry-wit comic relief, and Gotham City’s law-enforcement contingent: Commissioner Gordon, portrayed by Bob Hastings, renegade cop Harvey Bullock, a part knocked out of the park by character-actor extraordinaire Robert Costanzo, and patrolwoman Renee Montoya (played by Liane Schirmer), a character created by the series producers who would soon make her way into the comics as well.

While Gordon, Bullock and Montoya would always remain firmly in the background, the characters would occasionally be given a chance to shine, such as in “P.O.V.,” the series’ nod to Kurasawa’s RASHOMON.

As for Gordon, he wouldn’t receive a true spotlight moment until “Over the Edge,” from the program’s second series, which to my mind is probably the best and most shocking episode ever produced. More on that one later.

Much like the comics, however, Batman is only as good as his villains, and BATMAN: THE ANIMATED SERIES did a marvelous job of translating Batman’s Rogues’ Gallery for animation, with far more hits than misses. In many cases, their version wound up being far superior to earlier versions, and often supplanted them not only in the public consciousness, but in the source-material comic books as well.

You can’t have a Batman series without the Joker, and BATMAN: THE ANIMATED SERIES provided probably the most well-rounded and satisfying portrayal of the Joker in any medium, comics included. As realized here, the Joker was both funny and terrifying, capable of being motivated by egotism as well as sheer insanity.

The Joker design seemed most inspired by Bob Kane’s original artwork, but what really made the character come alive was the voice, provided by Luke Skywalker himself, STAR WARS’ Mark Hamill. The part had originally been given to Tim Curry, but the decision was made to recast, with producers feeling that Curry, while sufficiently threatening, wasn’t providing the necessary madcap levity and humor for the part. Enter Hamill, who had already played a supporting role in an earlier episode, but had made his desire known to play one of the trademark villains. One audition later, including Hamill’s unforgettable rendition of the Joker’s laugh, and the part was his. Hamill’s Joker could be foaming at the mouth in an insane rant one moment, and then instantly switch gears into a witty charmer.

The first real sense that this series would be like no other, both in its maturity and in its portrayal of the Joker, came in the episode “Joker’s Favor,” written by Paul Dini and directed by Boyd Kirkland. The episode was the first Joker episode to air, in the first week of the show’s broadcast, and clearly set the tone for all Joker appearances to follow. The episode opens with average Gotham City schlub Charlie Collins driving home from work and complaining about his miserable life, just before being cut off in traffic. Enraged, Charlie catches up with the offending vehicle, pulls alongside it and curses out the driver (it even looks like he’s about to give him the finger) only to realize to his horror that the driver of the car is the Joker.

Charlie speeds off, terrified (“I just cussed out the Joker!”), only to find that the Joker is now in hot pursuit. Charlie’s car is forced off the road, and soon the furious Joker has Charlie by the lapels. Charlie begs for mercy, and surprisingly, the Joker agrees, plucking Charlie’s driver’s license from his wallet and informing him that one day, Charlie can do him a favor in return.

Jump ahead two years, as a newly escaped Joker decides he needs a little help in arranging a special treat for Commissioner Gordon, and pulls the dog-eared driver’s license from his pocket, saying he knows a guy “who’s dying to do me a favor!” When Charlie gets the call from the Joker, he’s changed his name and moved his family far from Gotham, but not far enough to evade the Joker’s reach. After all, says the Joker, “You’ve become my hobby!”

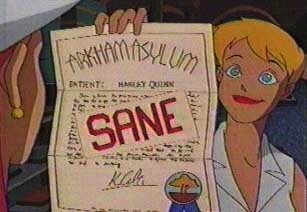

The episode highlighted both the Joker’s vengeful, murderous nature, and his dangerous, even whimsical unpredictability. Even better, the episode introduced Harley Quinn, the Joker’s “hench-wench,” a character that stands out as probably the best addition to the Batman mythology to come from the animated series.

Created by Paul Dini and Bruce Timm, Harley proved to be so popular that all of the BATMAN directors wanted to use her on their Joker episodes, as well as garnering the character several starring solo episodes as well. A former Arkham Asylum psychiatrist dragged into insanity by her undying love for the Joker, Harley’s devotion to the Joker grants him a heretofore unseen dimension, as he neglects and abuses her, yet cannot stand the idea of her eclipsing him or taking up with someone else. It’s made clear that the Joker does indeed bear considerable affection for Harley (or what passes for it deep within his twisted soul), making his mistreatment of her all the more heinous. Dini put it best in his book BATMAN: ANIMATED (a must-buy for fans of the animated series, by the way): “With Harley in his life, the Joker has become susceptible to the previously alien emotions of jealousy, inadequacy and humiliation. It couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy.”

As portrayed in a hilarious 1940s “screwball comedy” style by actress Arleen Sorkin, the Harley character comes across as spunky, sexy, smart, occasionally downright mean, just plain crazy and all too human. We begin to see hints of Harley’s (and Sorkin’s) emotional range in episodes like “Harlequinade,” (written by Paul Dini and directed by Kevin Altieri) in which Harley makes a deal with Batman to help him track down the Joker, who’s managed to acquire an atomic bomb, in exchange for her release from Arkham.

Along the way, Harley distracts a roomful of gangsters who are planning to kill Batman, with a knockout musical number, “Say We’ll be Sweethearts Again,” about a woman in love with a violent, abusive heel. (You’d think the song was written for the sow, but it’s actually from a 1930 MGM musical…)

When Harley discovers that the Joker was planning to leave Gotham and set off the bomb without her, well, hell hath no fury like a clowngirl scorned.

Harley’s character gets even more development in “Harley’s Holiday” (again from Dini and Altieri), in which the hapless henchgirl earns her release from Arkham Asylum, only to overreact to an incident in a snooty dress shop and accidentally wind up in the middle of an inadvertent kidnapping scheme, with Batman and Robin, Detective Bullock, gangsters and even the U.S. Army on her tail. After much mayhem, Batman returns Harley to Arkham, and Harley asks him why he tried so hard to keep her from getting killed. In response, Batman hands her the dress she was attempting to buy: “Because I had a bad day once, too.” Good stuff.

Harley also began a partnership of sorts with fellow Bat-villainess Poison Ivy in the episode “Harley and Ivy,” written by Paul Dini and directed by Boyd Kirkland. Ivy had made numerous appearances in the series previously, starting with her first appearance in “Pretty Poison” (written by Dini and Michael Reaves, directed by Boyd Kirkland), which introduced her as a bitter, vengeful eco-terrorist posing as D.A. Harvey Dent’s fiancee so as to get revenge on the man who built the prison that nearly eradicated a plant species. The Ivy design by Lynne Naylor was primarily based on the original comic-book costume, simplified for animation, with a hint of Tex Avery influence to it. Diane Pershing’s sultry voice work would shift on a dime to icy cold or hysterical, keenly conveying the character’s insanity.

Although some of the Ivy stories were somewhat uneven (her turn in “Eternal Youth” as the proprietor of a health spa that preys on rich, non-environmentally sound Gothamites was more than a little predictable), the combination of the Ivy and Harley characters in “Harley and Ivy” added a new dimension to both.

Booted out by the Joker in a fit of pique, Harley embarks on her own criminal career, and stumbles across Poison Ivy robbing a Gotham museum at the same time she is. Working together, the two easily fend off the police and escape, and set off on a crime spree that sets Gotham on its ear.

The papers dub them “the new Queens of Crime,” and soon the Joker, furious that Harley’s exploits have eclipsed his own, is determined to track down Harley and get her back (as well as take the loot). The episode is wickedly funny, (in scenes such as the newly liberated Harley blasting a carful of leering boors with a bazooka, or Harley seeing the face of her “puddin'” in a plate of Ivy’s vegetarian cuisine) —

–and surprisingly mature in content, not only for things like Poison Ivy kicking the Joker square in the balls, but also for the surprising amount of time that Harley and Ivy are shown hanging around in their underwear. Oh, and Batman shows up, too.

Come on back next week for part two of our look at the Dini/Timm/Burnett Batman animated universe…

Comments are closed.