From Comic Books 101: The History, Methods and Madness (published by Impact Books), written by Chris Ryall and Scott Tipton:

“The Bronze Age: Early 1970s—Early 1980s: Comics see a slight darkening in tone, reflective of the Vietnam-era climate. Stories cover real-world issues, such as drug abuse and politics, and overall, superhero comics become more realistic.”

One could argue that Marvel’s Master of Kung Fu series was borne out of an attempt by the House of Ideas to cash in on the kung fu craze of the 70s. One could speculate that Marvel was simply chasing the dragon. Look no further than the Wikipedia entry for Shang-Chi: “Marvel had wished to acquire the rights to adapt the Kung Fu television program, but were denied permission by the show’s owner, Time Warner, owner of DC Comics.”

Steve Englehart, the writer credited with creating Shang-Chi (alongside artist Jim Starlin), recounts the character’s inception much differently in his introduction to The Hands of Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu (Marvel Omnibus Volume 1). According to Englehart: “In the spring of 1973, ABC was trying out a weird TV show called Kung Fu with three episodes, one month apart (no binge-watching then). One episode had aired without catching either Jim’s or my attention.”

He goes on to state that he, along with a small group at a party, decided to skip dinner because “an artist named Steve Harper…was going to stay and watch this new TV show.” Englehart continues:

“We were intrigued, we all watched it, and Starlin and I said, “We’d really like to do something like that.” As a writer, I was mostly interested in occupying that headspace. As a writer-artist, Jim liked that and the martial arts combat.

“We went to Roy Thomas, Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief, and proposed our series. Roy was not impressed; martial arts was not his thing. But he was at least intrigued by our enthusiasm, so he did his E-I-C thing and said he’d okay it if we incorporated Fu Manchu, a more traditional Asian character, as a sales draw.”

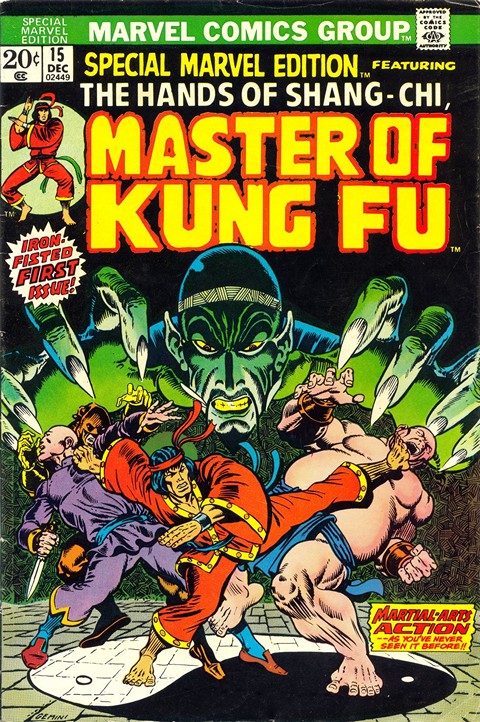

From there they were off to the races. Judging by Englehart’s version as written in the introduction of the omnibus, they weren’t chasing the dragon, so much as they running neck and neck with the dragon, introducing Shang-Chi, the son of supervillain Fu Manchu (a character himself licensed, from Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu novels), in Special Marvel Edition #15 (a title that Marvel originally published up to that point to double-dip on reprints). After Special Marvel Edition #16 was published, Englehart says: “Kung fu just exploded! The TV show had caught on, and so had we, and almost literally overnight, it was everywhere. Editorial wisdom said to change our title to Master of Kung Fu.”

As hungry as ever to keep chasing trends, if not inventing them, Marvel would force its magic dragon to multiply in the hopes of hatching more golden eggs for the publisher, with Roy Thomas and Gil Kane creating Iron Fist, and Englehart and Starlin being asked to crank out additional Shang-Chi stories for a new title, Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, which was a black-and-white magazine that included, among other things, reviews of kung fu flicks and interviews with martial arts instructors.

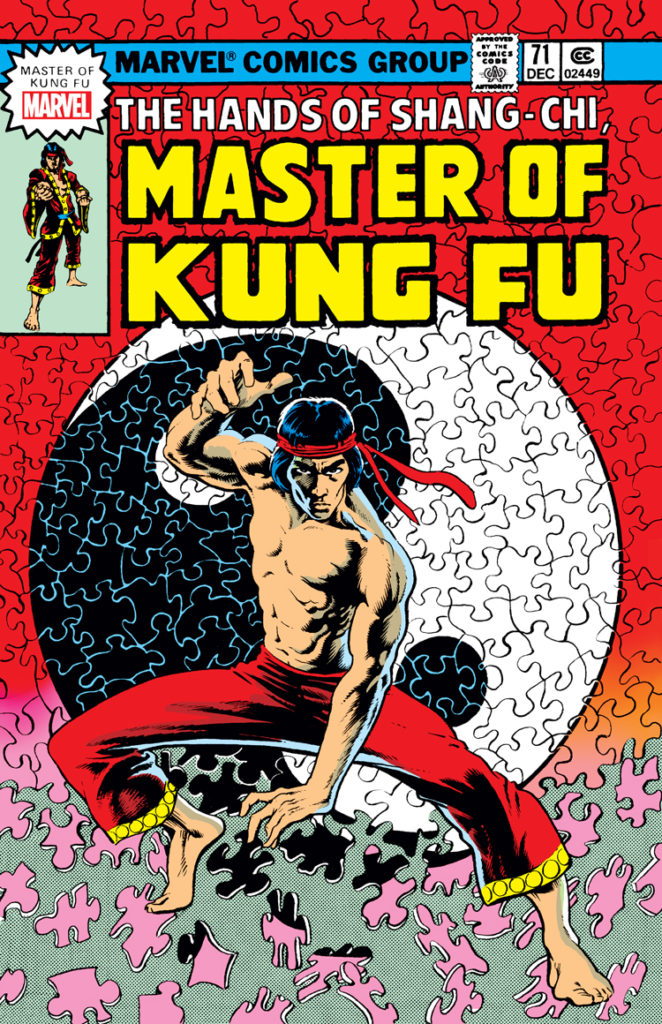

Artist and co-creator Starlin left the title after just three issues, but not without leaving his mark on the original title. Master of Kung Fu #18 would see artist Paul Gulacy pick up where Starlin left off, seemingly without missing a beat. But could Shang-Chi survive the one-two punch of both creators leaving the book? Marvel, and readers, would soon find out, as Englehart’s run would end with the completion of Master of Kung Fu #19. Doug Moench enters the fold as writer beginning with The Hands of Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu #20. Everyone was kung fu fighting, indeed.

Englehart wrote (again, from his introduction):

“Both the color comic and black-and-white magazine became monthly, and they ordered up a Giant-Size quarterly as well, and a black-and-white Special. Though gratified at this confirmation of Jim’s and my instincts, this was not at all what either of us had envisioned, so I followed him over the side.”

Englehart and Starlin’s Shang-Chi tale is, at its core, a fish-out-of-water story, and also deals with themes of self-awakening, with our hero forsaking the ways of his father, Fu Manchu, leaving behind the confines of his dojo for the very first time in his life, for the very foreign outside world. He lands squarely in the middle of the concrete jungle of 1970s New York City. Shang-Chi challenges the notion of nature versus nurture. After being raised to become a human weapon of vengeance under the watchful eyes of his father, with an upbringing steeped in discipline, devotion, and tradition, Shang-Chi finds himself on a path of self-discovery, questioning his very existence as he attempts to step out of his father’s violent shadow.

The Englehart/Starlin run is nothing short of dazzling. Their work elevates what could have easily been nothing more than a David Carradine Kung Fu knock-off. Instead it’s a knock-out, nimbly weaving between the throwback pulp adventure of Shang-Chi and Fu Manchu (along with a cast mixing new characters, Sax Rohmer’s characters, and even Marvel guest star Man-Thing in Issue #19) playing that ever-so-deadly game of kung fu cat-and-mouse, to something deeper, more meaningful and even philosophical.

The real world rears its head and is ever present in the pages of Shang-Chi’s first arc. Issue #18 sees the 1970s Gas Crisis as a plot point, with Fu Manchu mixing altered gasoline to sell “cheaply to the energy-starved Americans” to be released from the exhaust pipes of cars “into the air across America, to hang unsuspected as part of their smog” so that “in three months, the concentration will be such that all of America” will be Fu Manchu’s to command. That’s just one of the attributes that finds this book at home in the Bronze Age, and relevant even today.

Although the Englehart/Starlin combo on the Shang-Chi title amounted to a few scant issues in the grand scheme of things, the seeds had been planted, with the core book lasting a remarkable 125 issues, taking its final bow in June of 1983. Television’s Kung Fu series had an initial run from 1972-1975. If the battle was one measured by rounds and endurance, it’s clear that Shang-Chi was the victor, possibly far exceeding the wildest expectation of its creators (along with Marvel’s).

Regardless of the impetus behind the book’s creation, Shang-Chi is about more than where it came from (speaking of the book and the character), both literally and figuratively. For fans of comics, Bronze Age or otherwise, it’s a journey highly worth taking, and a series worth seeking.

Comments are closed.