Death is an occurrence that is very familiar to the average comic book reader. What is just as familiar, consequentially, is that death is not final in the eyes of the average comic book reader.

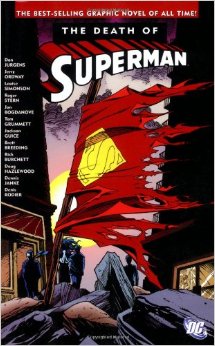

The first major resurrection of a comic book hero was in 1986. Marvel brought back X-Men’s Jean Grey after her death in The Dark Phoenix Saga six years beforehand. It is worth noting, however, that at the time, editor Jim Shooter said that this death was intended to be permanent. Jean’s story experienced severe alterations of previously established facts in continuity to facilitate the character’s return. (And for you kids at home that is known as applying retroactive continuity, or “retconning” for short). While this character is now spectacularly well known for her perpetual cycle of mortal coil comeback tours, it was DC Comics who is credited for blowing the proverbial casket wide open in 1993 with their profoundly publicized book, The Death of Superman. Unlike the death of Jean Grey, the intent of this book was to bring Superman back at the end of the story. The result of this reasoning forever broke the way death could be handled in comic books.

After the success of this book, DC Comics found themselves able to bring back some of their most beloved characters, finding reasons here and there for them to rejoin the ranks for justice. But once this door was opened, an issue began to arise. What is the consequence to bringing these people back? One foot tethered to the realm of the living and the endless fight for justice with the recognition of having the other foot in the grave, these superheroes often took on a different tone with their return. There was also the issue of legacies, those who had taken up the mantles of former heroes and villains after the deaths of these characters. For a while, in traditional John Wayne hero fashion, many of these reborn individuals pushed down their feelings and soldiered on. Not to say that no one dealt with these consequences, but that it had yet to be recognized on a universal scale. And what is life and death, if not universal? But after the resurrection of beloved scarlet speedster Barry Allen in 2008, (returning after a record 23 years of being dead), it was time for everyone to take a spin on the therapy couch and talk it out.

So in 2009 the whole DC Universe saddled up in Geoff Johns’ epic cross over event, Blackest Night.

Now when I say epic, I’m not just tossing that word around. Almost 100 issues worth of Green Lantern comics alone were being plugged as recommended reading going into the launch this crossover. (Don’t worry, you do not have to read almost 100 issues of Green Lantern comics to understand what is going on). Every nook and cranny of the DC Universe was touched by its effects. In the way that Death of Superman changed the way we think about death in comic books, Blackest Night gave us a whole new way to look at life.

I would also be remiss if I did not take a moment to mention that this crossover houses what are arguably some of Hal Jordan’s best one liners. Lots of rainbow jokes.

But I digress. We’re here to talk about some Lantern stuff. Let’s get weird.

Welcome to Lantern Stuff 101. Way back at the dawn of everything there was darkness, then there was light. The darkness fought back against this bright insurgence, and, as a result, the blinding white light of the universe was splintered into the color spectrum. These colors were the full force of the emotions that make up all life in the universe, and, consequentially, each life contributes to this Emotional Spectrum. All of these emotions could be collected and condensed into a source of power. Throughout the ages, they have become the lanterns that power the Colored Corps: Red for rage, Orange for avarice, Yellow for fear, Green for will, Blue for hope, Indigo for compassion, and Violet for love. Some of these Corps—such as the Green Lanterns—have used this condensed power to help the universe by acting as a sort of galactic police force. Others—such as the Yellow and Red Lantern Corps—use their power for conquering and devastation. Honestly, though, until Blackest Night, they mostly just all sat around fighting each other in a series of weird, perpetual intergalactic space feuds.

Preludes to Blackest Night showed the discovery by Green Lanterns Ash and Saarek of a Black Central Power Battery in Sector 666 of space. Two gruesome hands appear, killing the two Lanterns as the battery calls for “flesh,” and a barrage of black rings fly into space. These rings are powered by the original darkness, Death, and will not stop until they have consumed all universal light or, rather, every emotional being that keeps the spectrum lit. The rings find their way to Earth, directed by Nekron, the personification of death, as well as his right hand, Black Hand.

Superheroes and villains who have been killed over the years suddenly start being resurrected by the black power rings that fall to Earth, seeking out those who hold great emotional ties to them. They strive to evoke the highest emotional response they can from the living; ultimately consuming the hearts of their victims after they have been incited to their emotional peak. The extinguishment of these emotions at their nexus is what begins to charge the black power battery and, ultimately, Nekron.

The story followed many heroes and villains from all walks of Earth, causing them to face something that most heroes choose to not talk about:

What do we do when death itself comes back to haunt us?

Characters who had been mourned were not only coming back but were also taunting the living to evoke their emotional responses. Wonder Woman was forced to once more face her greatest regret, Maxwell Lord, a man who she had murdered in a broadcast seen around the globe (as seen in The OMAC Project, 2005), an act that cost her reputation and friendship with Superman and Batman. Mera, Queen of Atlantis, must combat her deceased husband and children, forcing her to deal with the fact that she is the last of the Aqua-family to survive and that she is—ultimately—alone. Ray Palmer, aka The Atom, comes face to face with his ex-lover, Jean Loring, who (during the 2004 mini-series Identity Crisis) suffered a mental breakdown and murdered longtime friend, Sue Dibny, wife of the Elongated Man. Ray has been living poorly with the results of this betrayal since.

These are only three of the numerous examples of what kind of devastation Blackest Night wrought upon its characters. Good and evil alike were being resurrected for the first time on the grandest scale of its time, and everyone is forced to deal universally with the consequences, not just through fighting but also by coming to terms with the resulting emotions. The learning experience that comes out of a story such as this is that those consequences do not have to destroy you. They are important to explore, and—if you can work through those emotions and come through to the other side—you truly are a hero.

The end result of these dealings with death in Blackest Night is eventually finding the White Lantern, which has been hidden on Earth since the dawn of time. The Lantern Corps come to Earth, deputizing some of the planet’s heroes through the power of their accepted emotions in the face of death. Wonder Woman takes on the mantle of an avatar of love for the Violet Lanterns; Mera becomes an avatar for the rage of the Red Lanterns; even the Atom embraces compassion for his troubled lady love and becomes an Indigo Lantern. By accepting the emotions that they feel, they become stronger and are able to beat back the Black Lanterns and unearth the full power of the White Lantern, the culmination of the whole of the Emotional Spectrum and the concentration of the power of Life in the universe. The result of this victory is that the resonance of the White Lantern is so great that some of the heroes and villains whom Nekron had brought back to live as the undead are suddenly granted full life again—permanent resurrection.

So with all this—death, life, and resurrection—a serious question is posed: How does dealing with all of this resonate with the reader? After all, these stories are for us; so, what are we supposed to take from them? Blackest Night shows its audience that what makes a hero isn’t just about punching/shooting/eye laser-beaming stuff. Being a hero is about overcoming adversity—not just physically but also emotionally—something that is often considered a bit taboo in current times. This is why this cross over event was so different and important in the wake of The Death of Superman. Dealing with death is, sadly, a part of life and something that everyone can relate to, super-powered or not. Death and life in Blackest Night showed that the human side of beloved heroes is what makes them so heroic. It’s okay to have feelings about life and death, and it is important to talk about them. And when those super human and super-powered sides are united, what they represent can become immortal.

That’s what makes superheroes so super, right? The sense of ageless immortality that comes with dying-too-young-but-always-coming-back-to-fight-the-good-fight is a power far more resonant and resolute than anything else the universe can produce. So often at the death of a character we roll our eyes now and say, “I give it a year, they’ll be back.” While that may be true, the fact that they can overcome life and death to be resurrected shows how resilient they are in our hearts and minds.

Melinda-Catherine Gross is a writer out of Burbank who she assures you is just as nerdy as she looks.

Comments are closed.