Bill Peet (1915-2002) is not a name that most people would know. His name is normally lost in the conversation about bigger people. In this case, the bigger person is Walt Disney.

Peet is responsible for some of the most iconic imaging in Disney’s early films. He cut his teeth on Pinocchio, Dumbo, Fantasia, and Song of the South; he created the mice of Cinderella and the “Once Upon a Dream” sequence from Sleeping Beauty. His work is most prevalent in The Sword in the Stone and 101 Dalmatians, which he wrote, designed and storyboarded.

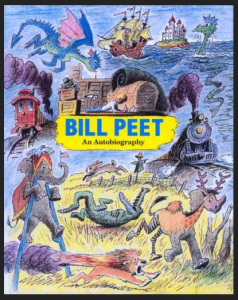

Bill Peet: An Autobiography, a mixture of prose and original artwork, is Peet’s chance to shine among all the other unsung talents of animation’s early years. Published in 1989, Peet spends the majority of the book in his formative years at Disney, which gives a fascinating look into the production of some of the studio’s early classic animated films. His autobiography is at once a fascinating account of the beginning of Disney’s animation domination and a testament to Peet’s skill as an artist. At times, it is as much the story of Walt Disney as it is of Bill Peet.

Peet joined the studio at the age of 22 in 1937, the year Snow White and the Seven Dwarves was first released in theaters. He would remain at the studio for 30 years, working his way up from an in-betweener (the grunts who fill in the blanks of animation) to the position of story man. What is funny is that this almost did not happen.

After his initial work on Snow White, Peet settled into his in-between position, drawing hundreds and hundreds of Donald Ducks. This job would eventually tax Peet’s sanity and one day, he blew up in the middle of artist bullpen, screaming “NO MORE DUCKS!” He stormed out of the animation annex, yelling and swearing the whole way home. Though he had not offered a formal resignation, Peet had no intention of returning to the company.

It would be later that Peet would realize he had left his only jacket at work and would have to go back the next day to collect it. This is when he would be truly freed from Donald Duck, as he was accepted onto Pinocchio after pitching monster designs for the upcoming feature (designs for a sequence that would eventually be scrapped).

This is when the specter of Walt Disney would start to loom over Peet.

Perhaps it is because of his place in animation history or just his natural presence, but Walt Disney seems more alive as a Bill Peet drawing than in old photos.

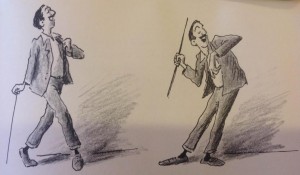

During the ’40s and ’50s, Peet worked his way up from character designs and being a nameless part of the animation team (literally, as Peet recounts his frustration at being left out of the Pinocchio credits). Peet witnessed the two sides of Walt Disney; the playful creator and the angry bear. Each movie seemed to dictate which Walt would lead the team through the next animated feature. Peet would be subjected to Walt’s fury one day then receive tender encouragement the next.

Peet’s final two films, 101 Dalmatians and Sword in the Stone, were the biggest showcases of his talents. Having finally made it to the story man position Peet strove to reach, he was able to impress Walt and was given a great deal of creative freedom. Dalmatians came at a perilous time for Disney and their animated films.

Sleeping Beauty, while now held as a classic and a financial success, had done poorly in its initial release and left the company’s future in animated films uncertain. But Walt wanted to push on and gave Peet a copy of Dodie Smith’s book, The Hundred and One Dalmatians, telling Peet “It might make a good animated feature.”

As tended to be the case, Walt was right and Peet’s biggest contribution to the Walt Disney canon was released in 1961. Its success set the studio back on track and allowed Peet to continue on with The Sword in the Stone. Considering the magic Walt had been spinning for nearly four decades, it should not be a surprise that Peet used his boss as inspiration for the great wizard Merlin.

But for all the goodwill he achieved from these two films, it would all come undone with The Jungle Book. Kipling’s book is a much darker story than the animated film Disney would eventually release and Peet wanted to stay true to that feeling. Walt had other plans, and over a few story conferences, the two began to clash over the vision of the story. The last time Peet ever sees Disney, they have a heated argument during a storyboard presentation. “If you want to see some real entertainment, then see Mary Poppins.”

Those are the final words Peet would hear from his boss. That night, Peet left the studio to pursue his writing career and unlike the first time he quit, he did not look back. Walt would die a year later and Peet would find out in the newspaper.

Peet had a long road to becoming an author, struggling to find his voice as a writer and finding time away from his work at Disney. It wouldn’t be until he moved to the shorts department (a result of his arguing with Walt) that he would be able to distill his ideas into books.

It would be over 20 years into his time at Disney, in 1959, that Peet published his first book, Hubert’s Hair Raising Adventure. He would go on to author over 30 children’s books, including The Caboose Who Got Loose, Kermit the Hermit, and Goliath II, which was originally done as an animated short in 1960.

In the world of Walt Disney, one must give their total focus and hold nothing back for themselves. If he hadn’t left the animation company, he would never have had the time to create the stories that would define the second half of his life.

Comments are closed.