Post-disaster stories are based on one of two things: either the world we know was overcome or it was never good enough in the first place. Lately we seem to prefer the latter, where we could have stopped the zombies or climate change or the new plague if we hadn’t been so lazy, corrupt, or pig-headed.

But there was a time when people saw the future as a bigger, bolder version of the present, or at least a present on the bigger, bolder canvas of space.

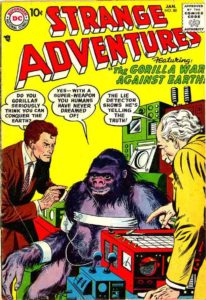

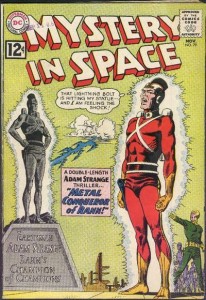

Take two DC science fiction titles: Strange Adventures (published 1950-1973) and Mystery in Space (1951-1966).

They started when the atomic bomb that ended World War II had happened only six years previously. In 1949 the Americans discovered the Soviets had detonated their own atomic bomb. McCarthyism had just begun. The trends in comics were not superheroes, they were horror (about a third of all titles), romance, cowboys, and science fiction. This was the era of EC comics. This was the era when Timely and Dell each outsold DC.

People were gathering to condemn comics, legislation was being proposed, and Wertham waited in the wings. Many people wanted comics controlled, destroyed, or both. They wanted legislation to restrict the sale of comics to children. They pitched comics into bonfires with no sense of irony whatsoever.

Everything seemed set to make those two comics a blip on the radar, soon to be forgotten. It didn’t work that way. Between them, those comics introduced Adam Strange, Captain Comet, Animal Man, Hawkman, Darwin Jones, and others.

There was also a post-atomic disaster series, the Atomic Knights. But every story showed a problem just as it ended (with the exception of those unsuccessful fascists, the Blue Belts). So the tales open with, for example, hunger and rampant mob hatred of scientists as problems. But a scientist comes with a kind of metal detector with antenna and finds cans of food. The Atomic Knights form and take out the Black Baron and open the food stores to the general populace. The Atomic Knights told the story that, even if America falls, it will be recreated in its own image. Good ideas will not die.

Well, good ideas may die, but fun ones will always survive. There were stories that should never have gotten anywhere, but they did. In part they spoke with an optimism that in a more cynical age truly rankles some commentators who have to tell us the stories are silly or products of their right-wing times. But let’s take a second look at these stories.

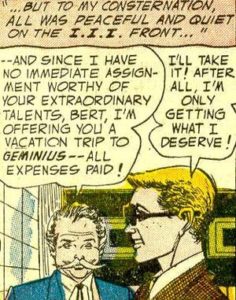

In the 22nd century, Bert Brandon has an ordinary job: he sells insurance for Interplanetary Insurance Inc. It seems the III took the advice any actuary would give any insurance company: get big because lots of customers spreads the risk. And, let’s face it, all random events will not be under control by the 22nd century.

Bert is a bespectacled kind of guy, and in one story travels to a new planet, Gllyn, which is a newly discovered planetoid beyond Jupiter. Gllyn always faces one side to the sun, and that side is occupied by the Lullies who have humanoid or butterfly forms. The dark side is occupied by the Kroques. The two sides are eternal enemies even though they never seem to have met.

Bert Brandon sells insurance to the queen – and yes, gravity, atmosphere, and temperature are all Earth-like – and then to her subjects. The problem is, the humanoid forms die and a butterfly form emerges. They say the original form is dead, so pay up. Bert doesn’t want to.

This has been called the horrible insurance people being cheap. But the new butterfly form seems to have the memories of the previous humanoid form. There is a question whether death has really occurred. Bert Brandon sees an issue and wants to take it to court. But the Kroques now invade in force. The Lullies have no weapons. Bert grabs a giant telescope lens and hits the Kroques with light, frying the lot of them.

The Lullies are grateful, so they accept the (I think legally unavoidable) proposition that changing form and leaving behind a husk is not death. The Kroques, it turns out, needed that much light to become the firefly people. They’re willing to sign up for life insurance even though they, apparently, are immortal, too.

Silly thing, and so capitalist it is to be hated. Unless you look at it as an allegory. The people (us) who live in light need only see that light comes to those who live in darkness. That light is the only weapon that needs to be arrayed against the Soviet Union. Then those in darkness will become our friends once light reaches them.

Bert Brandon appeared in Mystery in Space in issues 16 to 25. Not all the stories can be said to be analogies, but they all centered on the simple premise of making an ordinary living in an extraordinary universe.

Another case of a slightly less ordinary job, and a series which largely replaced the insurance seller, was Space Cabbie (sometimes spelled space cabby). Space Cabbie was his job and as much of a name as he ever got. His job was as a cab driver (number 7433) who would take you anywhere in the solar system from Mercury to Pluto (which still counted as a planet).

Like many cab drivers in the fifties, he was a war veteran. He served in the Bored Wars of 2146, he had trouble making ends meet (so he took a job in the twentieth century and apparently transferred the money directly instead of putting it in the bank, waiting, and getting rich). He also had to worry about getting into trouble with the Interplanetary Police. Worse than problems with the police, of course, were problems with space-bandits (sic), the odd thief, and duplicates (possibly clones) of himself.

Space Cabbie started out just as a narrator, working in the same way as but in a different genre to the Crypt Keeper in EC. But the driver in the space ship based on a Cadillac (look at the fins) was interesting enough to repeat.

Space Cabbie made his living the way many of his readers and the fathers and (less often) mothers of his readers made their living. But through it all there was a sense of hyperbole and fun that permeated the stories but with an overtone of struggling to survive in a harsh universe.

Space Cabbie originally appeared in Mystery in Space issues 21, 24, and 26 to 47. Then in 1999, Space Cabbie came back to co-star in Starman. Starman Jack Knight went into the future and met all the obscure science fiction characters that writers James Robinson and David S Goyer could fit in. Space Cabbie appeared in Starman number 55. Now, it seems he will be revived again in Kieth Griffen’s Threshold.

Good ideas may die, fun ones never do.

The Space Museum had its run and came back again and again. The idea of a place where the most important exhibits in several worlds was just too good to pass up. The Space Museum began as a frame to different stories. Howard Parker would take his son, Tommy, to the museum, Tommy would ask about an exhibit and Howard would tell the story about it.

Howard knew everything about every item in the museum. In that he was the perfect 1950’s father, though the series only started in 1959. One kind of tumult had ended and another was about to begin. But in the future, Howard knew about the items in the museum, partly because he stole most of them.

After the original series ceased, the Space Museum kept popping up in the background of other stories. Though there was never an indication where the museum was or when the Parkers lived (except it was appreciably in the future) it wound up in Metropolis in the time of the Legion, where (though not when) Booster Gold stole the equipment he needed to become a twentieth-century superhero. But the things Booster Gold stole were not the kind of things originally exhibited in the museum. The original stories told mostly of ordinary things like a magpie, a blond hair, a toy soldier, a knitting needle, and a pocket watch. These ordinary things in each case helped save the Earth or sometimes another world. Sure, there was a spaceship, and the obligatory being of pure energy. But there was also a picture of Tommy because he saved his parents from aliens when he was three, and another time Tommy’s own mother used the knitting needle to save the world.

In the end the Space Museum did not celebrate space travel the action, but the courage that space travel required. And it celebrated how even the least of people or things could accomplish something of great value. It just takes heroism, daring, and self-sacrifice. It’s not a message we give to children, now: we expect them to be exemplars by being exemplary followers of some leader of some group or another.

Certainly, they would not expect three Interplanetary Boy Scouts, including Tommy, of course, to remember what Tommy’s dad had said about exhibits and use them to thwart aliens out to steal Earth’s energy.

In Secret Origins in 1990, some thirty-one years after the original story, we learn where the Space Museum got its start: Howard Parker stole a bunch of stuff and used it to stop some invading aliens. Realizing you have to know history to know the present, the Space Museum was founded.

Space Museum was published in Strange Adventures, with twenty stories published between 1959 and 1964.

Star Hawkins is a hard-boiled detective in the late 21st century. The stories have been lampooned as being “space westerns.” In other words, the kind of story that could have been a cowboy story but it was given a veneer of the future, like trading six-shooters for ray guns. This implies what we face in the future will be completely unlike what we faced in the past. In other words, we will not expand into new dangerous areas where there is enough space for bad guys to hide, kind of like the wild west. By that argument, the Internet is safe.

But Star Hawkins was a silly example of a silly genre. The late 21st century is not so far away as when the stories were written. There’s only 70 years to go, now, not 120. Like all of his il,k he is very good at solving cases, not too hot at collecting fees or saving money. It is a trick from the beginnings of detective stories, so writers don’t have to make the detective seem hard-hearted by actually demanding to be paid for what he does.

Again, as was common, he had a secretary who was also underpaid, but showed loyalty to the detective after going short of wages time after time, bailing the guy out off the clock (with her own money), and stopping the bad guys without getting credit (or paid). Money was dirty, and in the dark city that had seen better, or at least more honorable, days, the detective drew a line.

Star Hawkins’ secretary, Ilda, is one of a kind, except she’s a robot. Her number is F2324. Star Hawkins buys her as the series opens. During the series he sometimes pawns her and she sits in a cage with the other pawned robots. Silly sight gag, of course.

Of course, her model of robot is declared obsolete. Star Hawkins saves the envoy from another galaxy who had been kidnapped and thus prevented an intergalactic war in which they could get to us and we couldn’t get to them, so we were going to lose. In gratitude F2324’s model is allowed to exist and not be smashed into little pieces for another ten years, but she was still considered obsolete. There’s a silly story of a world run by chuckleheads where anything not the latest and the newest gets thrown on the scrapheap whether the old model can do the job or not.

But in the end, Star Hawkins finally catches a break. He had gained a reputation of catching zips (slang for crooks) due to various cases. Money is better. But then he stops the zip who is trying to kidnap heiress Stella Sterling. Turned out to be Automan, a robot character over 130 years old in story chronology. Automan is being hunted by a gang of zips so they can use the unique asteroid metal he is made of to make a weapon. Automan is trying to get the descendant of his creator to safety . The zip, Bio-room, has a quarter of a billion price on his head – though Stella Sterling gets the reward.

But Star and Stella hit it off. They become a couple, despite being named like fraternal twins, and found the Hawkins-Sterling Academy of Robot-Detection, teaching robots to be private eyes and getting Hawkins a regular paycheck. In the meantime, Ilda and Automan become a couple, but can’t marry because they’re robots. The government is so impressed it outlaws the junking of robots and allows robots to marry. It is the usual silly element of science fiction that robots, being able to think and having consciousness, should have rights to go with that. Rights go with consciousness, not organic structure. Silly.

So, in the sixteen silly stories in Strange Adventures, Star Hawkins covers questions of enslavement. He cannot mention or even walk on the same street as black people, but he can cover the same issues in robots: sentient beings who are a form of chattel. He covers age discrimination, the idea that you can’t just get rid of someone who can do the job because they’re older. Lots of people in their forties who want a job can identity with that. And he covers the idea that two conscious beings who want to form a permanent couple should be allowed to do so. No, we don’t have any problems with that sort of question in our enlightened era. Must have just been something from that silly, silly story from a past, ignorant era.

Mind you, to believe that, you have to go to all the blacks, all the older people who would like a job (or a full time job), and all those people not allowed to marry – whomever they might be – and tell them they don’t count. Stories about them should not be written. That would be silly.

Comments are closed.