I met Ray Bradbury in a dark basement in the suburbs of Long Island. He hit me on the head with a tremendous force and sent me reeling backwards through a plywood door and into an old washing machine. I sat stunned on the floor of my mother’s laundry room, listening to the growl of the churning clothes and staring into the darkness, frightened.

You are a child in a small town. You are, to be exact, eight years old, and it is growing late at night…

I’d been reaching for the very top of the vast bookcases my mother had rigged under the house, grabbing blindly for the next “Encyclopedia Brown” adventure. Mom had introduced me to these wonderful “choose your own” adventure books that summer and I couldn’t get enough of them. My fingertips grazed Mr. Brown, but knocked Mr. Bradbury loose instead.

There were hundreds of books on those shelves, in stark contrast to my father’s house across the country, its rooms devoid of the written word in any form. She packed them atop wooden slats held up by large cinderblocks. They were in no discernable order, which made it all the more exciting. What’s a book really, without the thrill of the hunt preceding it?

If my brother were there, he’d have easily grabbed it for me. Older, taller, stronger. He had gone back to our father when the summer came to an end while I chose to stay behind for good and all. I missed him.

Skipper is your brother. He is your older brother. He’s twelve and healthy, red-faced, hawk-nosed, tawny-haired, broad-shouldered for his years, and always running. He is over on the other side of town this evening to a game of kick-the-can and will be home soon. You both sit there listening to the summer silence and staring out into the dark, dark, dark.

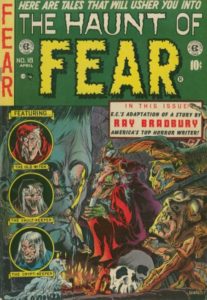

My head was bleeding a bit and it throbbed something awful, so I stayed there on the floor awhile, listening to the hard-at-work clothing and cracking open this angry, violent book that had attacked me. Its cover alone brought the room a sudden chill.

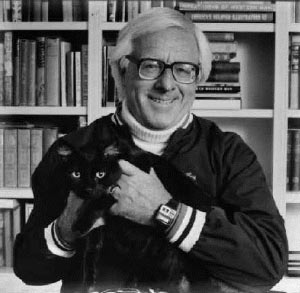

The story was called “The Night” and it took me altogether by surprise. It was my first experience reading a story where what the author chose to say was almost as emotionally charged as what he didn’t. It spoke to me. It spoke to my life experience up until that point. I stopped after every page, looking up and half expecting the author to be standing in front of me, laughing.The basement was my place. I’d turned it into a sanctuary, complete with bed, television and the requisite stacks of comic books. I spent most of my time down there (much to my mother’s dismay). Sure, it was spooky, but what isn’t when you’re a young boy?

It had been many years since I’d really lived with my mother. She got my brother and I for the brilliant summers, but the rest of the year was reserved for my father and his off-kilter existence.

I suppose we were still getting to know each other. Being a father now, I can’t begin to imagine how difficult it was for her, sending us off on a plane at one end of a year and seeing us return on the other, stretched, sprouted, transformed.

You and your mother are all alone at home in the warm darkness of summer. The town is so quiet and far off, you can only hear the crickets sounding in the spaces beyond the hot indigo trees that hold back the stars…

My father was devastated when I called to tell him that I wasn’t coming home. He felt ambushed, betrayed. I tried to explain that I wanted to just “be with mom for awhile,” but that wasn’t altogether true. How could I tell him how stifled I felt in our house? How little promise there was in its illiterate rooms? How little wonder?

I couldn’t put into words how frightened I was to leave him and to let go of my brother’s hand. But I also couldn’t bring myself to explain how empowered I felt taking my mother’s.

“I wonder where your brother is?” Mother says after a while. “He should be home by now. It’s almost nine-thirty.” Mom sits down a moment, then stands up, goes to the door, and calls.

“Skipper. Skipper. Skiiiiiipperrrr.” Her calling goes out into the summer warm dark and never comes back. The echoes pay no attention.

And as you sit on the floor, a coldness goes through you. You notice mom’s eyes sliding, blinking; the way she stands undecided and is nervous. All of these things.

You take her hand. Together you walk down St. James Street. In the back of the church a hundred yards away, the ravine begins. You can smell it. It has a dark sewer, rotten foliage, thick green odour. A jungle by day. A place to let alone at night.

You are only eight years old, you know little of death, fear or dread. Death is your little sister one morning when you awaken at the age of seven, look into her crib and see her staring up at you with a blind blue, fixed and frozen stare until the men come with a small wicker basket to take her away. Death is when you stand by her high chair four weeks later and suddenly realize she’ll never be in it again, laughing and crying, and make you jealous of her because she was born. That is death.

I had read five pages and I was terrified, mesmerized, giddy and dreadfully sad. Five pages! It felt like fifty.

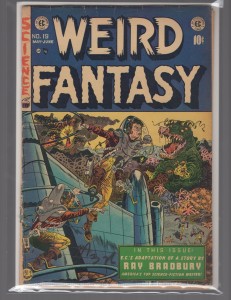

Some of the greatest stories are the shortest. The greatest television shows. The greatest movies. And of course, the greatest comics.

The Ravine.

Here and now, down there in that pit of jungled blackness is suddenly all the evil you will ever know. Evil you will never understand. All of the nameless things are there. Later, when you have grown you’ll be given names to label them with. Here at this spot, civilization ceases, reason ends, and a universal evil takes over.

You realize you are alone. You and your mother. Her hand trembles. Is she, too, doubtful? Does she, too, feel that intangible menace? Is there, then, no strength in growing up? No solace in being an adult?

If you should scream now, if you should holler for help, would it matter?

Thank God for storytellers who can write such short, sharp, shocks that reach out and grab the lapels of young readers and old alike. Who don’t belittle those still developing minds. Who push the boundaries and inspire them to work their imaginations that little bit harder.

It is indeed a seduction of the innocent. A beckoning into a greater understanding of not just the world, but of themselves. Sometimes, what’s required actually is a “snare,” an “enticement” and a “charming attraction” to coax growing minds to blossom. And sometimes, it isn’t just the light that makes them grow. Sometimes, it’s a hint of the dark.

There are a million small towns like this all over the world. Each as dark, as lonely, each as removed, as full of shuddering and wonder. The secret damp ravines. Life is a horror lived in them at night, when at all sides sanity, marriage, children, happiness, are threatened by an ogre called death.

There are a million small towns like this all over the world. Each as dark, as lonely, each as removed, as full of shuddering and wonder. The secret damp ravines. Life is a horror lived in them at night, when at all sides sanity, marriage, children, happiness, are threatened by an ogre called death.

Mother raises her voice into the dark. “Skip. Skipper!” she calls. Suddenly, both of you realize something is wrong. Something very wrong.

It is as if the whole ravine is tensing, bunching together its black fivers, drawing in power from all about sleeping countrysides, for miles and miles. In ten seconds now, something will happen. The crickets keep their truce, the stars are so low you can almost brush the tinsel. There are swarms of them, hot and sharp.

Growing, growing, the silence. Growing, growing, the tenseness. Oh it’s so dark, so far away from everything. Oh God!

At this point, I was huddled into a tiny ball, fingers jammed into my mouth as I tore my fingernails to shreds. I put the book down in my lap and considered throwing it into the corner and leaving the basement forever. Is this what reading is?! Is this what I have to look forward to? Constant anxiety about the next page, paragraph, word?

I cried. I cried for my parental tug-of-war. For my loneliness. For my brother, not there to look up to. For my sister, long since passed, who I would never, ever know. I cried, not knowing why.

And of course, I read on.

And then the quick scuttering of tennis shoes padding down through the pit of the ravine. Your brother, Skipper. “Hi mom! Hey!”

She puts away her fear, instantly. You know she will never tell anybody of it, ever. It will be in her heart though, for all time, as it is in your heart, for all time.

You walk home to bed in the late summer night. You are glad Skipper is alive. Very glad. You go to bed, shivering, beside your brother. You smell the sweat of Skip beside you. It is magic. You stop trembling.

Nine pages. The story was nine pages long. It was fierce and breathtaking and I was completely exhausted. It was everything a good novel should be. It had everything it was supposed to have. And it was over in a heartbeat.

Nine pages. The story was nine pages long. It was fierce and breathtaking and I was completely exhausted. It was everything a good novel should be. It had everything it was supposed to have. And it was over in a heartbeat.

Obviously, I went on to read every single piece of fiction Bradbury ever put to paper. And I carry those damn spaceship dreams to this very present day. But that night?

That night, I put the book down and went upstairs to the kitchen. I hugged my mother and helped her make dinner. I called my brother and told him I missed him. I sent my father love, even though he wouldn’t come to the phone. And I thought of my sister and all of the many wonderful things I would never fully understand.

Comments are closed.