One thing about Marvel Comics in the ’60s and ’70s: it had no compunctions about following the popular trends. After all, this was a company that survived the dark days of comics in the 1950s by pumping out tons of comics about whatever was succeeding elsewhere, not just in comics, but TV and film as well. Westerns all the rage? Marvel would crank out the Westerns. Kids flocking to the sci-fi movies? All space monsters, all the time. Even after Marvel had hit it big in the ’60s with its new line of superheroes like the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man and the X-Men, it still kept its eye on the popular culture, and didn’t mind at all trying to cash in on what was hot in the movies and on TV. When James Bond and THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. were all the rage, Marvel wasted no time in transplanting its WW II hero Nick Fury into the modern day and making him “NICK FURY, AGENT OF S.H.I.E.L.D.” And this wasn’t at all a bad thing, really; it kept the company looking vital and on the cutting edge, especially in contrast to DC’s more staid, traditional line of superhero magazines.

Marvel would continue this trend into the early 1970s. For example, with kung fu movies being all the rage in the ’70s, Marvel introduced their own kung fu superhero, Iron Fist (although it must be noted that, much like the producers of the television series KUNG FU, they still hedged their bets for maximum appeal with their core audience by making their protagonist white). What else was popular in the early ’70s? “Blaxploitation,” the theatrical trend of action movies targeted to urban African-American audiences, films like SHAFT, SUPERFLY and FOXY BROWN, in which strong, charismatic Black men and women kicked ass and took names, sticking it to the man, usually to a funk & soul-driven soundtrack. While they may not have been able to supply the soundtrack, Marvel recognized everything else about the formula, and swiftly put it to use in June 1972, with the debut issue of LUKE CAGE, HERO FOR HIRE.

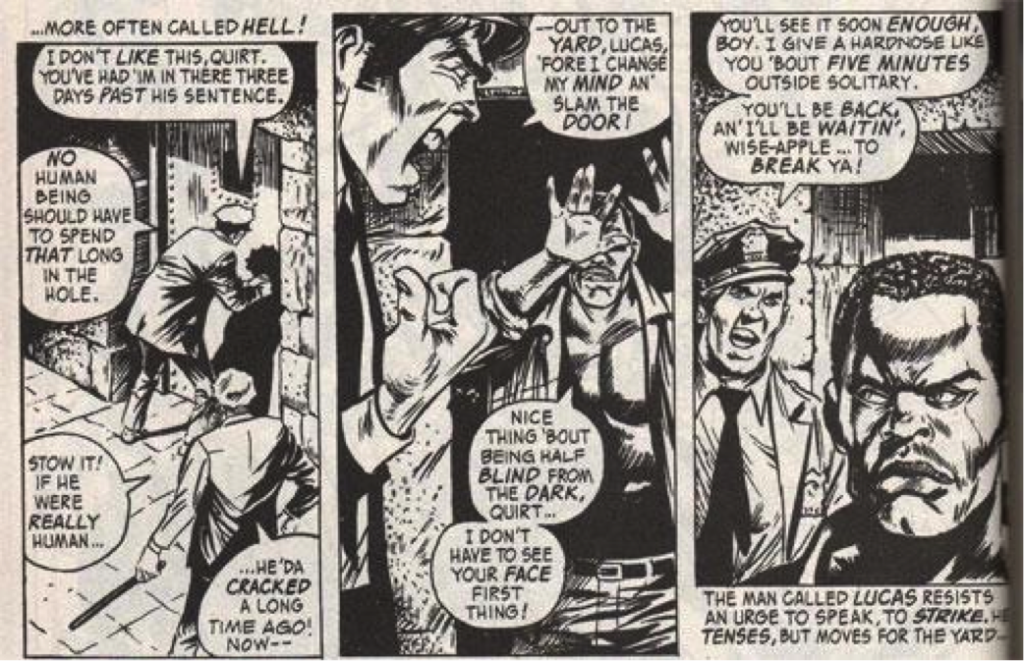

Written by Archie Goodwin and drawn by George Tuska (with design work on the character done by John Romita, Sr.), the first issue was notable not only on its own merits, but also because it marked the first Black character to have his own monthly comic book. (While both the Black Panther and the Falcon predated Luke Cage by a few years, neither one had been given a monthly series.) So who was this Luke Cage character? As with most things, it’s probably best to begin at, well, the beginning, so let’s pick things up in the opening pages of HERO FOR HIRE #1, whose story begins at Seagate Island Prison, a maximum-security penitentiary where we meet for the first time an inmate known only as Lucas, whose refusal to kowtow to the facility’s racist guards has gained him an undue amount of attention, most recently in the form of a lengthy stint in solitary.

Lucas’ anger doesn’t come only from the guards’ abuse, but also from a greater injustice: Lucas himself is innocent, framed for narcotics possession with intent to sell by his childhood buddy Willis Stryker, the two men’s friendship torn asunder by Stryker’s jealousy toward the woman Lucas loved. Not only that, once Lucas was convicted, Stryker’s car was attacked by rival dope-smugglers, and Lucas’ girlfriend was killed in the crossfire. However, trapped in Seagate, there’s not much he can do about it.

That is, until a reformer warden takes over at the prison, busts the captain of the guards (a weasel-faced hater by the name of Rackham) down to guard duty, and even gives Lucas a chance to get even with his tormentors:

No longer on the outs with the prison higher-ups, Lucas is given a chance at parole if he’ll participate in a medical experiment being undertaken by the prison’s physician, Dr. Noah Burstein. With the usual help from Stark Enterprises technology (is there anyone in the Marvel Universe Stark doesn’t have a contract with? Even the prisons?), Burstein is researching a process for stimulating human cell regeneration, with the idea being to counter nearly all disease, and perhaps even slow or halt the aging process. So Lucas hops into Doc Burstein’s electric bathtub, only to meet up with an ugly surprise: that ratface guard Rackham is back, and he jams the hatch and whirls the controls up to overload, trapping Lucas in an electrochemical batch far longer and more intensified that the doctor has intended.

Unable to take the agony of the process, Lucas strikes out, smashing open the chamber and backhanding Rackham, who was about to open fire, across the room. In a fit of anger at the prospects of his parole fading away due to his striking a guard, Lucas punches the wall, only to find that not only did it not hurt his hand at all, but the concrete wall cracked beneath the blow. Amazed, Lucas pounds away at the wall, smashing clean through it and making his escape.

Cornered at the island’s rocky cliff, prison guards open fire on Lucas, riddling him with bullets, and he falls to the river below. To his amazement, the only sign of the bullets on Lucas’ body are a few bruises. While up above at the cliffs, Lucas’s bullet-ridden shirt convinces the guards that he’s surely dead, and the search for him is called off.

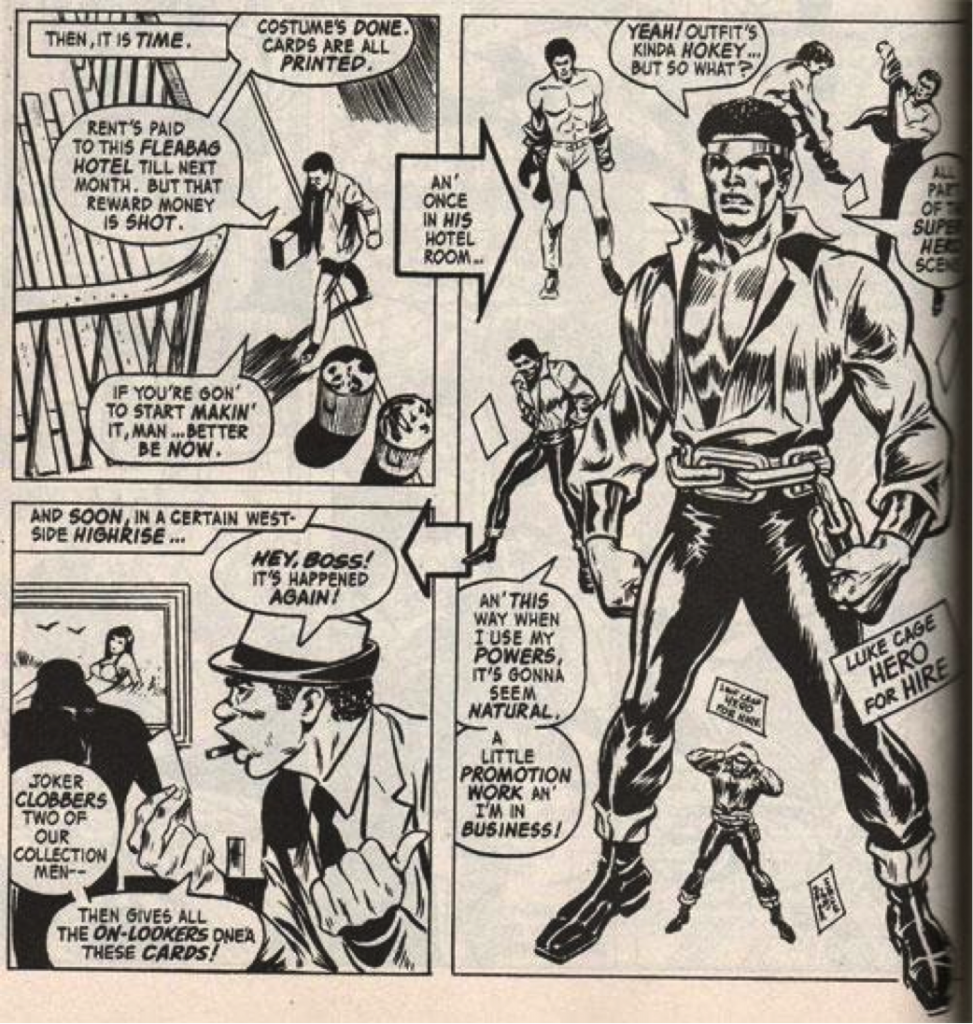

Now free and believed dead, Lucas slowly makes his way back to New York in order to exact his revenge on Willis Stryker, while also despondent over how he expects to survive, not wanting to show off his newfound power for fear of being discovered, and unable to get a regular job without risking his fugitive status. When he offhandedly intervenes in an armed robbery at a diner and is given a cash reward by the owner, Lucas begins to realize how he can solve both his problems at once.

Using the reward money, Lucas stops at a costume shop and puts together a superhero-style outfit (granted, a slightly more pimped-out one, particularly the yellow silk shirt), adopts a new identity in the name of “Luke Cage” – the surname acting as a reminder of his past – and spends the last of his reward cash on business cards for his new venture, which he wastes no time in spreading around the neighborhood as he busts local pushers and extortionists: “Luke Cage – Hero for Hire.”

This, by the way, gets the attention of the local crime boss, who just happens to be the man Luke Cage is looking for: his old friend turned bitter enemy Willis Stryker, who in the intervening years as developed both a deadly skill with throwing knives and a fondness for snakeskin suits, and has taken to calling himself Diamondback. Catchy.

In reading this, I was both surprised and pleased at how well the story holds up.

Don’t get me wrong – it’s most definitely a product of its time, and the references to the then-hot Blaxploitation trend are very apparent. But the basic story and characterization is solid and satisfying, and Luke Cage comes across as a compelling, likable character, not just as a racial stereotype. Much of his later overdone catchphrases (such as the cringeworthy “Sweet Christmas!”) are absent here, as is the slightly embarrassing attempt at giving him an urban dialect that we’d see at the hands of many extremely white writers. Instead, Cage sounds like a reasonably intelligent if primarily street-educated young man, who’s been ill-treated by the world, but doesn’t blindly hate because of it. I wouldn’t be surprised if Brian Michael Bendis had looked to these early issues for cues to Cage’s characterization in NEW AVENGERS, because this definitely feels like the same man.

It’s also refreshing in retrospect that, unlike so many of the African American superheroes of the era, Luke Cage doesn’t have the annoyingly obvious “Black” codename, like, say, Black Panther, Black Goliath and Black Lightning. Even when the character changed his name later in the book’s run, it was “Power Man,” once again, not specifically a reference to race. Despite the theatrical source of inspiration, Luke Cage to me always felt like a superhero who happened to be a Black guy, as opposed to being a “Black superhero,” which I think has had a lot to do with his continued popularity over the years.

And on the subject of race, it must be mentioned that this book didn’t pull its punches on the matter of racism and race relations. The racist guards at the prison are just that: flat-out unrepentant racists. And in later issues, Luke Cage comes up against white opponents who call him “Boy” and other racial slurs (and man, does that piss him off) – reading it now, this stuff is jarring, because popular culture has become so homogenized and politically correct in recent years. One have to wonder if it isn’t better to portray these types of unsavory characters in popular fiction for the unsympathetic ignorant fools that they are, and show them being defeated and their faulty ideals squashed, as opposed to the tack that seems to be more common today: to close our eyes and pretend it doesn’t happen, for fear of offending the overly sensitive.

Next Week: Meet Luke Cage’s rogue’s gallery, plus Latverian bill collecting.

Comments are closed.