The 1970s and early 1980s were a golden heyday for comic book adaptations of popular films, and few could rival Marvel Comics in this regard. Marvel adapted a number of successful movies (and a few not-so-successful ones along the way), some as serialized miniseries, others as oversized comics or novel-sized digests. Several were offered up in multiple formats, enabling fans to add more acquisitions to their shelves—and Marvel, of course, to add more margin to its profits.

Among the more unique titles was the Marvel Treasury Edition, a series of 28 oversized tabloid comics published from 1974 to 1981 that typically reprinted previously published stories, while occasionally presenting new material. The largest of Marvel’s formats, it measured 10 inches by 14 inches (nearly twice the size of a standard comic book) and frequently provided art galleries at the back, resulting in many copies being dismantled so fans could hang them up as posters—which, naturally, increased their scarcity since they were effectively ruined at that point.

The Marvel Treasury Editions were primarily superhero-based, focused on characters such as Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, Thor, Howard the Duck, Conan the Barbarian, Hulk, and more. Several issues, however—both the Treasury Editions and the smaller yet still oversized Marvel Special Editions and Marvel Super Specials—adapted popular space-based science-fiction films. It’s these that appealed most to non-superhero fans.

The Marvel Special Edition series lasted for six issues, published between 1975 and 1980, with numbering handled rather haphazardly. Both The Spectacular Spider-Man and the first Star Wars edition, for example, were identified as issue #1, while the second Star Wars edition and The Empire Strikes Back were called issue #2, and the third Star Wars edition and Close Encounters of the Third Kind were each labeled issue #3. This can make collecting Marvel Special Editions a bit confusing, not to mention maddening for those with obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

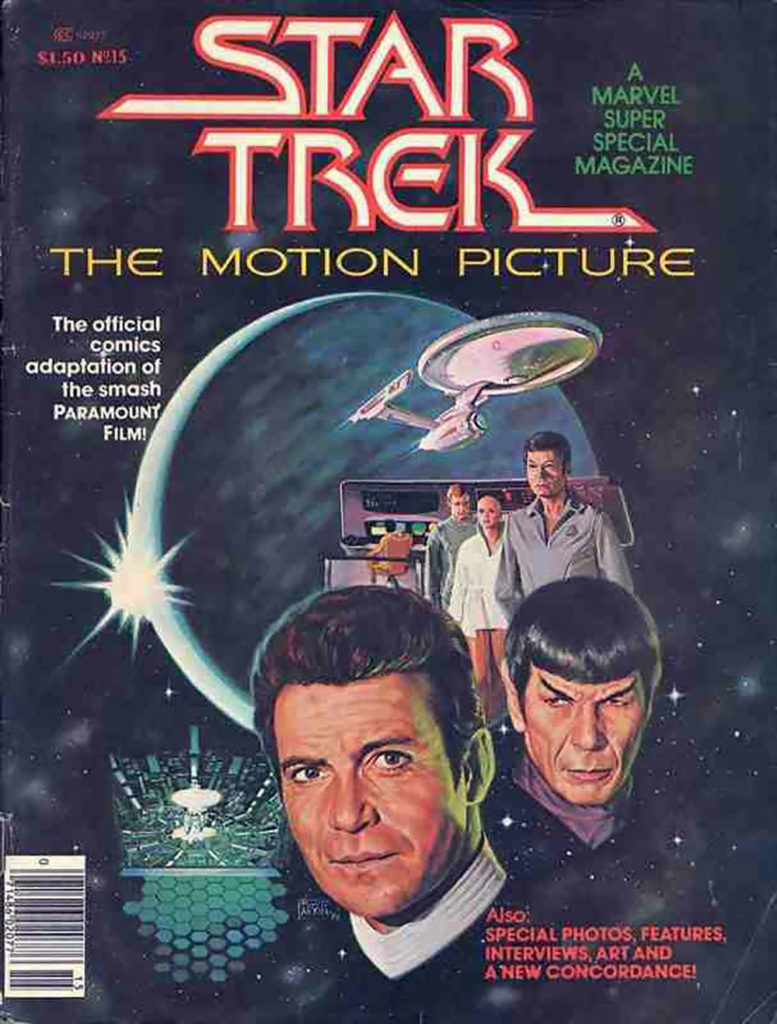

The Marvel Super Special line proved to be the most long-lived, producing a total of 41 issues between 1977 and 1986, covering everything from science fiction and horror to James Bond and Indiana Jones, to musicals and the rock band KISS. It was the most diverse of Marvel’s various Treasury-style series, for sure. Where else could one find an adaptation of The Dark Crystal alongside comic-book versions of The Muppets Take Manhattan, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and Annie?

Perhaps the most well-known Marvel Special Editions were the three Star Wars issues. The first two, from 1977, reprinted Marvel’s now-classic adaptation from writer Roy Thomas and artists Howard Chaykin and Steve Leialoha, first presented in monthly Star Wars issues #1-6 and here broken up into a pair of three-chapter chunks.

Since the pages were of a different height-to-width ratio than standard comics, several panels ended up being cropped at the bottom, sacrificing the characters’ feet (and foreshadowing Rob Liefeld’s infamous 1990s covers). The third edition combined the first two as a single, complete collection, and all three were released as both Marvel and Whitman comics, which were distributed to different outlets but featured the same content.

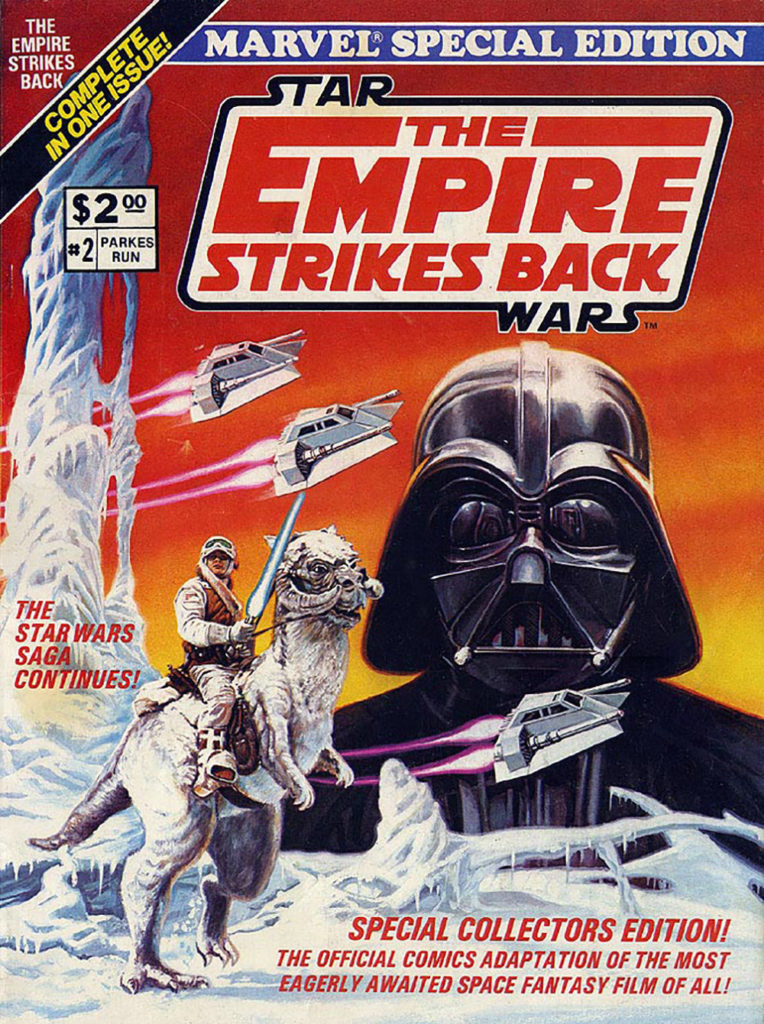

Two years later, in spring 1980, Marvel released a Special Edition collecting its six-part adaptation of The Empire Strikes Back (originally in Star Wars issues #39-44), from the genius writer-artist team of Archie Goodwin, Al Williamson, and Carlos Garzon.

This edition was also collected in Marvel Super Special #16. Yet another collection, the novel-sized Marvel Comics Illustrated Version of The Empire Strikes Back, featured the infamous “purple Yoda” from the monthly comics, but his appearance was correctly drawn in the Special Editions to match his onscreen look. Although no Marvel Special Edition was released for Return of the Jedi, Marvel’s four-issue miniseries based on that film was collected in Marvel Super Special #27, as well as in other formats.

This edition was also collected in Marvel Super Special #16. Yet another collection, the novel-sized Marvel Comics Illustrated Version of The Empire Strikes Back, featured the infamous “purple Yoda” from the monthly comics, but his appearance was correctly drawn in the Special Editions to match his onscreen look. Although no Marvel Special Edition was released for Return of the Jedi, Marvel’s four-issue miniseries based on that film was collected in Marvel Super Special #27, as well as in other formats.

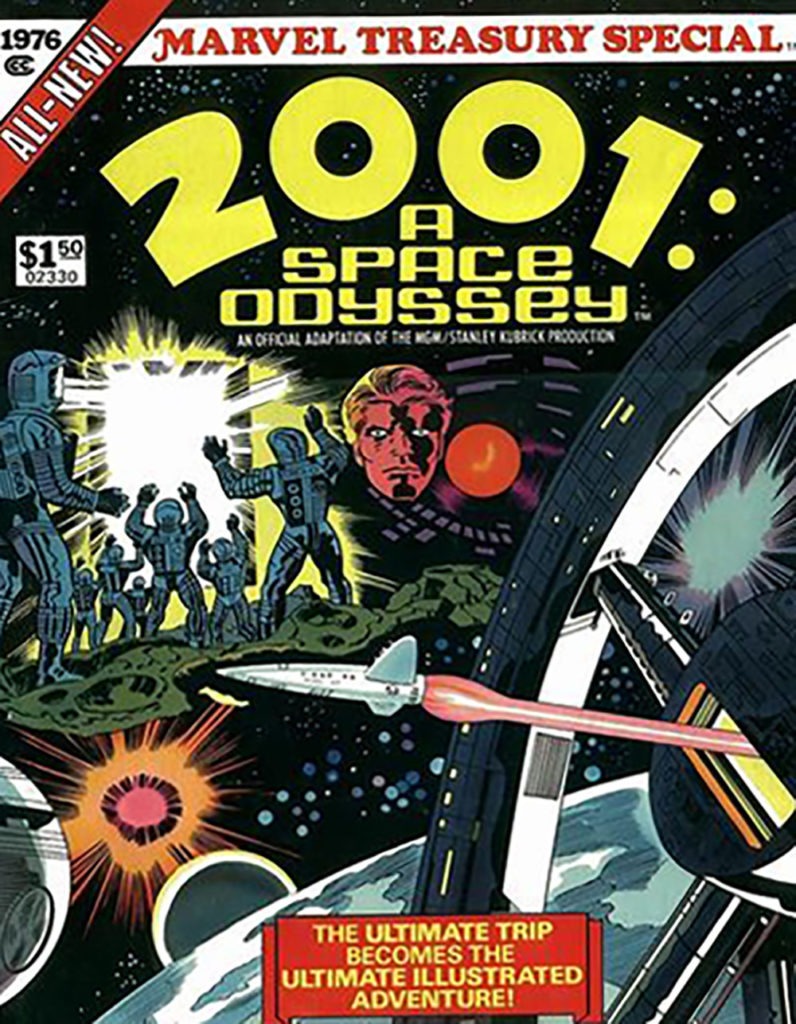

In 1976, the publisher released a Marvel Treasury Special by Jack Kirby adapting Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, based on the novel by Arthur C. Clarke.

The story closely adhered to the film’s events, though Kirby incorporated dialog from both Clarke’s novel and an early-draft film screenplay, resulting in HAL 9000 sounding more colloquial in its speech patterns than the artificial intelligence did on the big screen. The comic also delved into the characters’ emotions and thoughts—a sharp departure from Kubrick’s almost sterile onscreen approach to the material. All combined, this makes Marvel’s 2001 one of the most fascinating adaptations of that era.

The story closely adhered to the film’s events, though Kirby incorporated dialog from both Clarke’s novel and an early-draft film screenplay, resulting in HAL 9000 sounding more colloquial in its speech patterns than the artificial intelligence did on the big screen. The comic also delved into the characters’ emotions and thoughts—a sharp departure from Kubrick’s almost sterile onscreen approach to the material. All combined, this makes Marvel’s 2001 one of the most fascinating adaptations of that era.

This particular Treasury Special led to a short-lived monthly comic book, also by Kirby, that continued the story beyond the movie’s events. The sequel film, 2010: The Year We Made Contact, did not receive Treasury Special treatment, though it was adapted as a two-part miniseries that was then collected in Marvel Super Special #37, from writer J.M. DeMatteis and illustrators Joe Barney, Larry Hama, and Tom Palmer.

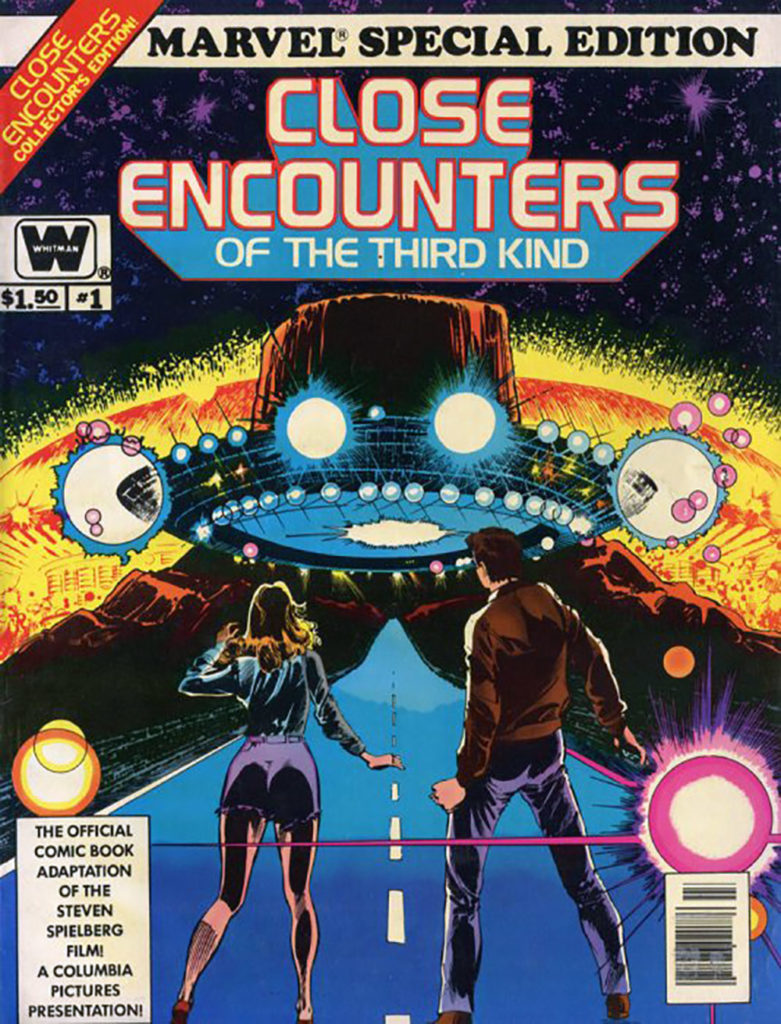

The year 1978 saw the release of a Marvel Special Edition of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. This edition repackaged Marvel Super Special #3, which featured a film adaptation from Archie Goodwin, Walt Simonson, and Klaus Janson.

Though beautifully drawn, the adaptation skewed away from the characters’ onscreen likenesses, most likely for legal reasons. As such, it can be a bit jarring to read for those unfamiliar with the hassles comic publishers often faced when adapting movies.

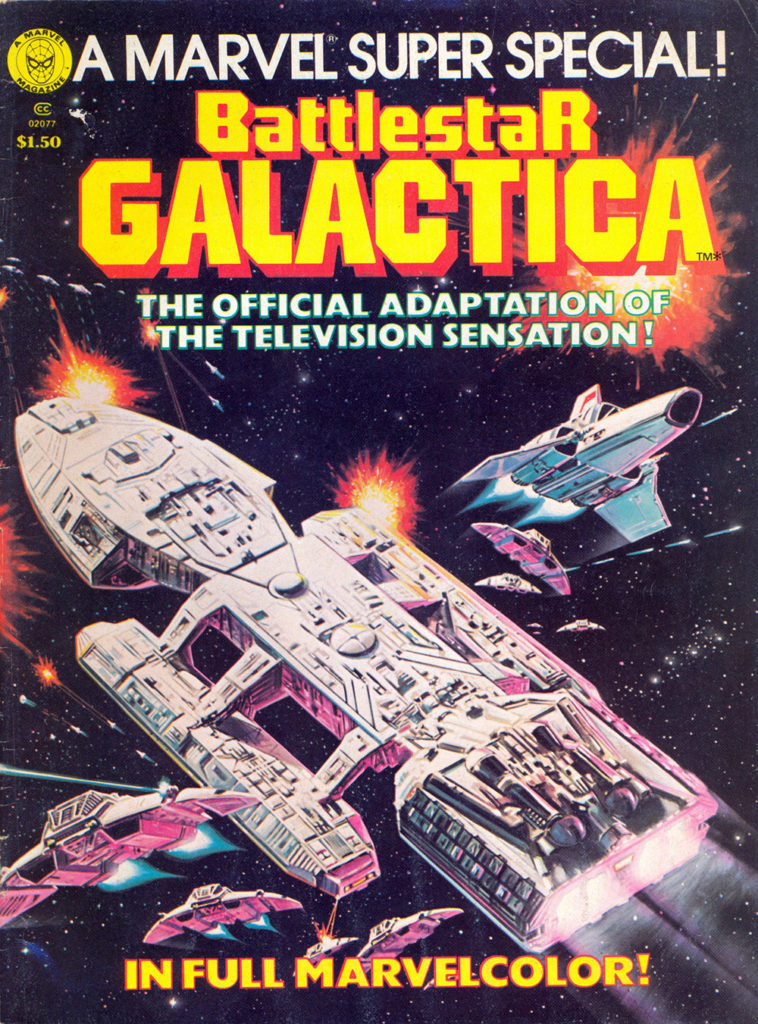

Other science-fiction-based Marvel Super Specials included issue #8, reprinting the adaptation of Battlestar Galactica‘s opening three-parter, “Saga of a Star World,” by Roger McKenzie and Ernie Colón; issue #14, featuring an adaptation of the film Meteor from writer Ralph Macchio and illustrators Gene Colan and Tom Palmer; #15, collecting the Star Trek: The Motion Picture adaptation from monthly Star Trek issues #1-3, by Marv Wolfman, Dave Cockrum, and Klaus Janson, which famously retained the film’s original ending; and #22, with Goodwin, Williamson, and Garzon adapting Blade Runner. Marvel must have liked Harrison Ford movies, as Super Special #18 adapted Raiders of the Lost Ark, while #30 presented Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

The Super Special series also offered Marvel’s takes on other sci-fi movies, including #28, which adapted Krull, courtesy of David Michelinie, Bret Blevins, and Vince Colletta; #31, which featured The Last Starfighter as adapted by Bill Mantlo, Blevins, and Tony Salmons; #33, containing Marvel’s version of The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!, by Mantlo, Mark Texeira, and Armando Gil; and finally #36, which brought Frank Herbert’s Dune to the four-color realm, thanks to Macchio and Bill Sienkiewicz.

On a side note, it’s a shame Marvel never gave The Karate Kid the Marvel Super Special treatment. How amusing would it have been to have seen a comic adapting a movie starring Ralph Macchio, written by an entirely different Ralph Macchio? (No? Well… I would have found it amusing, at least.) Of course, the fact that DC Comics actually had a character called Karate Kid among its heroes might have legally precluded that option.

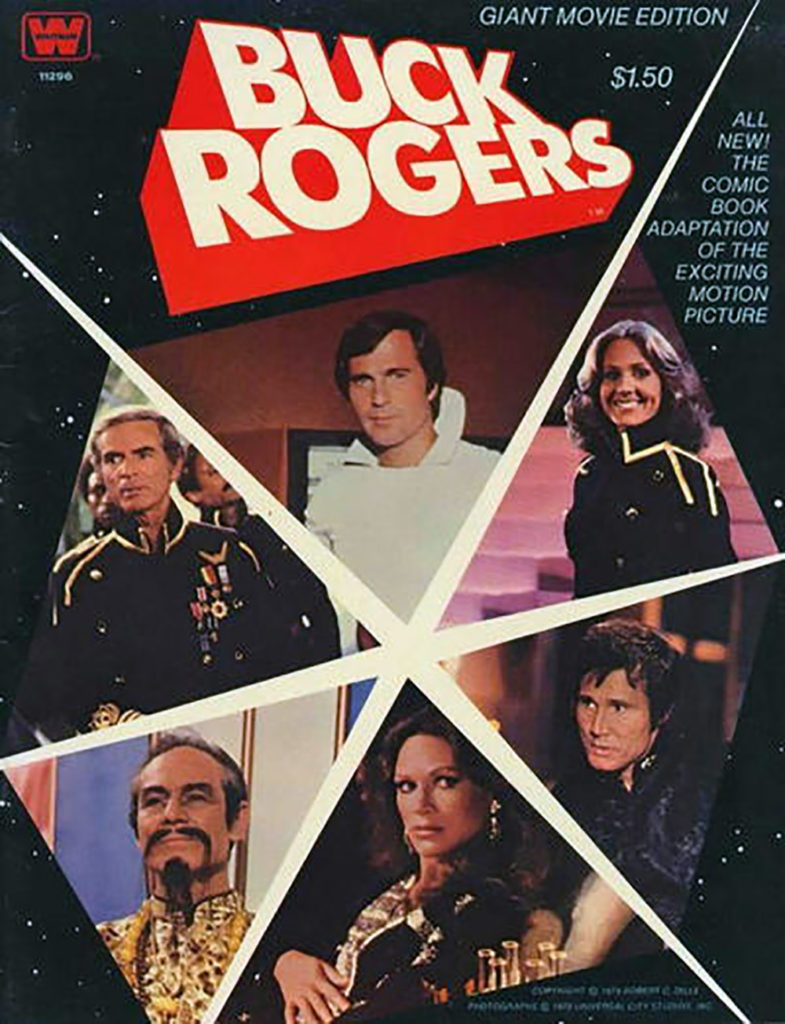

In addition, there was the Buck Rogers Giant Movie Edition, published in 1979, which was based on the 1979 Gil Gerard film Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

Adapted by Paul Newman, Frank Bolle, Al McWilliams, and Jose Delbo, this oversized edition included photos from the movie and a behind-the-scenes text article. Several of the above-noted Marvel Super Specials featured such extra content, in fact—it was a pretty common practice, since it gave readers who already owned the monthly issues a justifiable reason to double-dip and pick up the collected versions as well.

If you’re a fan of comic books based on science-fiction films, then you already know that Marvel Comics was among the best in the business at bringing our favorite silver-screen stories to the printed page (it comes as no surprise, then, that these days it’s the best at bringing our favorite stories from the printed page to the silver screen, via the Marvel Cinematic Universe). Other publishers, notably DC Comics, offered adaptations during that golden age of movie-based comics as well, but Marvel took things a step further by collecting them in a wide variety of unique and memorable formats. When it came to adapting movies to comic books, Marvel had little competition.

Sure, the Marvel Treasury Editions, Marvel Special Editions, and Marvel Super Specials can be difficult to fit on a comic-book shelf, but for those who enjoy unusual finds, leafing through comic books the size of an atlas certainly fits the bill. They’re definitely a product of their era—you won’t likely find any comics publishers producing such editions nowadays, simply because they wouldn’t sell well in the current market—and the larger size allows for closer viewing of smaller details one might miss with a standard-sized comic book. In short, Marvel Comics’ 1970s movie adaptations are a true treasure. So if you’re new to such adaptations and are trying to decide where to start, take my advice and make yours Marvel.

Comments are closed.