Our own Jud Meyers interviews Robert Silverberg, the Hugo- and Nebula-award-winning science-fiction author and Grand Master of Science Fiction on the occasion of the release of the new graphic-novel adaptation of his novel DOWNWARD TO THE EARTH from the publisher Humanoids.

Jud: Our community loves to discuss the beginnings of their romance with comic books and science fiction literature. Our childhood obsessions are sort of the base of the pyramid for all of us. Were you a fan of comic books as a boy?

Robert: Of course. My comic-book era covers ages six through ten or so, which is roughly equivalent to the years of World War II. But I was also reading prose books from a very early age. Eventually they came to have more to offer me than the adventures of Superman or Batman. The paperback boom was just beginning when the war ended in 1945, Pocket Books and the American version of Penguin Books as the pioneers, and when it did I shifted quickly from comic books to the very tempting 25-cent paperback books. (My Aunt Mary was very good about slipping me quarters to buy paperbacks.) But between 1941 and 1945 or so I read all the big comic books, the ones that now sell for millions of dollars, and, no, I didn’t keep my copies and retire on the proceeds of their sale years later.

Jud: Can you recall the first comic book you ever read that stayed with you?

Robert: The one that had the biggest impact on me was PLANET COMICS, around 1942, which set me on the path to science fiction. I had already discovered s-f through the Buck Rogers comic strip that ran in one of the Sunday newspapers, but it was PLANET COMICS that really got me hooked.

Jud: Strange question, but where did you find it? Sometimes, the place where we unearthed the initial treasure says a lot about who we were and who we developed into.

Robert: Sorry, no. More than 75 years ago and I just don’t remember. I do remember buying my first science-fiction magazine, in 1948, on a newsstand near my school in Brooklyn.

Jud: What about the first Speculative Fiction novel that made you stare off into the distance for hours?

Robert: H.G. Wells, THE TIME MACHINE. I was ten or eleven.

Jud: Were you the isolated kid that devoured stacks of books or did you have a “tribe” that you spent time with, developing a taste for what you did and didn’t like?

Robert: I was an only child, as was the norm during the Great Depression, and I was pretty much of a loner as a small boy. I had playmates, of course, but only children aren’t very big on sharing, and when it came to reading, which, of course, is a solitary pastime, I withdrew to my own room and made no effort to discuss what I was reading with others my age. Later, when I was twelve or thirteen and had discovered science fiction, I became much more sociable: I found others who shared my tastes, and we loaned each other magazines, talked about what we were reading, etc. And from there it was an easy move into the worldwide community that is science-fiction fandom in my teens.

Jud: Sometimes, the mechanics of your work are as fascinating as the work itself. Neil Gaiman writes everything in beat up notebooks and then just transcribes it all into a computer when it’s completed. Harlan Ellison still bashes away with two fingers at an old manual typewriter, carbon copies and white-out spilling everywhere. It’s hard to imagine you writing by hand considering the mountainous amount of work you produced from the pulps to the paperbacks to the fully realized novels. What was your system and did it change drastically based on the advancement of technology?

Robert: I would make a brief outline on the back of an old envelope and start typing away. Generally I would do just one draft, a sheet of white paper, a sheet of carbon paper, a sheet of yellow second paper, and read it through and make corrections, if necessary, by hand. For more demanding markets I would do a first draft on scrap sheets and then type out a second draft, which again I would correct by hand before turning it in. I was a touch typist, and a good one, but it was still a lot of hammering away, and in 1982, after undergoing the interminable ordeal of typing several drafts of a 900-page manuscript (LORD OF DARKNESS) I happily converted to working on a computer. My old typewriter still sits on a desk in my office but it’s there simply as an artifact.

Jud: Speaking of technology, I’m interested in your take on something in particular. My daughter has been making her way through the classics we all devoured so long ago. It’s a pleasure to watch her discover the source material for all of the television and film she and her friends bombard themselves with every day. Recently, she set down an old H.G Wells book she was reading, stormed into the kitchen and announced, “Scientists didn’t create the escalator, H.G Wells did!” We then debated the idea of whether writers could take credit as co-creators if their idea inspired scientists to bring those idea into reality. So many of the concepts you came up with in your books turned into practical things we use in our everyday lives that were fantastical ideas when you wrote them.

Robert: I’m a storyteller, not an inventor. I’m always amused when something I’ve written about in a story turns up as a real-world device or concept — my 1964 story “The Pain Peddlers” may have invented the reality TV show, which is not exactly something I ought to be proud of, and a lot of my stories back then offhandedly mention gadgets that we actually use today. But I have no illusions about the distinction between making something up and really inventing it. It’s one thing to say, casually, “Beam me up, Scotty” and another thing entirely to do the heavy lifting involved in building the device that makes the beaming-up possible.

Jud: What are your thoughts on this? Is “Speculative Fiction” and “Science Fiction” one and the same or does one inform the other?

Robert: They are the same thing. I think “Speculative Fiction” sounds a bit uppity, and I always refer to the field in which I wrote as “Science Fiction,” but I think “speculative fiction” is actually a more appropriate term, since there isn’t much science in a lot of science-fiction but the best stuff always deals in thoughtful “what-if” conceptualization, even if it’s not very gadgety.

Jud: Have you marveled over the years when something you dreamed up on the page actually appeared in your living room?

Robert: Many times. But when it goes out of whack I generally have to call a technician to fix it for me.

Jud: You’re known to be a sort of scholar among your contemporaries. Many of the greatest science fiction/fantasy writers of your generation had very limited education or training. They just fell into a time when there was a hunger for short stories and a fascination with the future by a culture trying to define itself. The idea that there were paperback vending machines in gas and train stations is almost impossible for the average young reader to imagine.

Robert: Most of my contemporary colleagues were older than I was, because I got such an early start as a writer, and so their lives were affected by the Depression and then World War II in a way that mine wasn’t. My adolescence was spent in prosperous peacetime and so I had a chance to go to college, a very good one, and I was much the better off for it as a writer. But very few of the other s-f writers of my era had that chance. Isaac Asimov had a college education, of course, but he had to fight very hard to get into the school I went to because of the anti-Semitic quotas of his day, fifteen years ahead of mine. Fred Pohl didn’t even finish high school, not that that kept him from being one of the greatest of s-f writers. Heinlein was educated to be a naval officer. A lot of others got an involuntary military education when they were pulled into the armed services for World War II without an opportunity for college. I’m happy to have had the education I had, and I’ve put it to good use in my work, but a really determined writer can manage to pick up whatever knowledge he needs on his own, if he has to.

Jud: Do you think we’ve lost something to the computer screen or has it opened up new worlds for young readers?

Robert: The computer is a miracle. Google alone is the key to all knowledge, if you know where to look. And word-processing is an invaluable time-saving tool for writers.

Jud: Has the science that writers like you dreamed into existence done some kind of harm to the practicality of studying words on a piece of paper held in two hands?

Robert: I don’t think so. Just the other day I saw a report that sales of e-books have leveled off because today’s readers still seem to like old-fashioned printed books. Gadgets like the Kindle are marvelous conveniences for people who load six or seven fat books on their machine before they go off on a trip, but I don’t think printed words are going to disappear in my lifetime.

Jud: Recently, I had the pleasure of reading Octavia Butler’s notebooks that were on display at the Huntington Library. In the margins of one of the pages was a note to herself. It read, “I am not a black, female Science Fiction writer. I am not a black, female writer. I am not a black writer. I am a writer.”

I know that Ellison, Bradbury, Bester and so many other science fiction/fantasy writers struggled with being defined by their genre, not by their ability to craft a story. Even “Dying Inside” was a struggle for many critics and readers to admit was a novel of great importance, not a great science fiction novel. It seems only writers like Vonnegut were able to win over the literary circles that mostly dismissed the speculative fiction arena.

You own the mantle of Grand Master of Science Fiction. You’ve won four Hugo Awards. Six Nebulas. You’ve written hundreds of science fiction stories. Literally millions of words on the page. Clearly, you’re among a handful of the greatest science fiction/fantasy writers in history.

Robert: Octavia Butler had special problems because she belonged to a bunch of minorities that were clamoring for special attention, and so people kept labeling her with her special identities. No doubt she was black and female and wrote science fiction, but the main point about her was that she wrote, and wrote well. I happen to be Jewish, but that’s no big deal in science fiction, which has produced Isaac Asimov, Alfred Bester, Robert Sheckley, Harlan Ellison, Avram Davidson, Stanley G. Weinbaum, and a slew of others. Otherwise I am white and male, so I don’t have to deal with identity politics. When someone asks me my professional background, I say “science-fiction writer.” If pressed, I let it be known that I wrote a lot of other things besides science fiction, but a science-fiction writer is what I set out to become when I was sixteen or so, and that is what I did become, and (unlike Vonnegut, who was a mainstream writer who wrote some pretty good science fiction, and unlike Olivia Butler, who really was a science-fiction writer but didn’t like being pushed into categories), I have no problem with identifying myself as a science-fiction writer.

Jud: Is there a quiet part of you that wonders about an alternate universe where Robert Silverberg had the same success in a strictly fiction genre, void of spaceships and alien races and brain transference? Just grounded stories about humans and their relationships here on earth? Would there even be a difference between the two men?

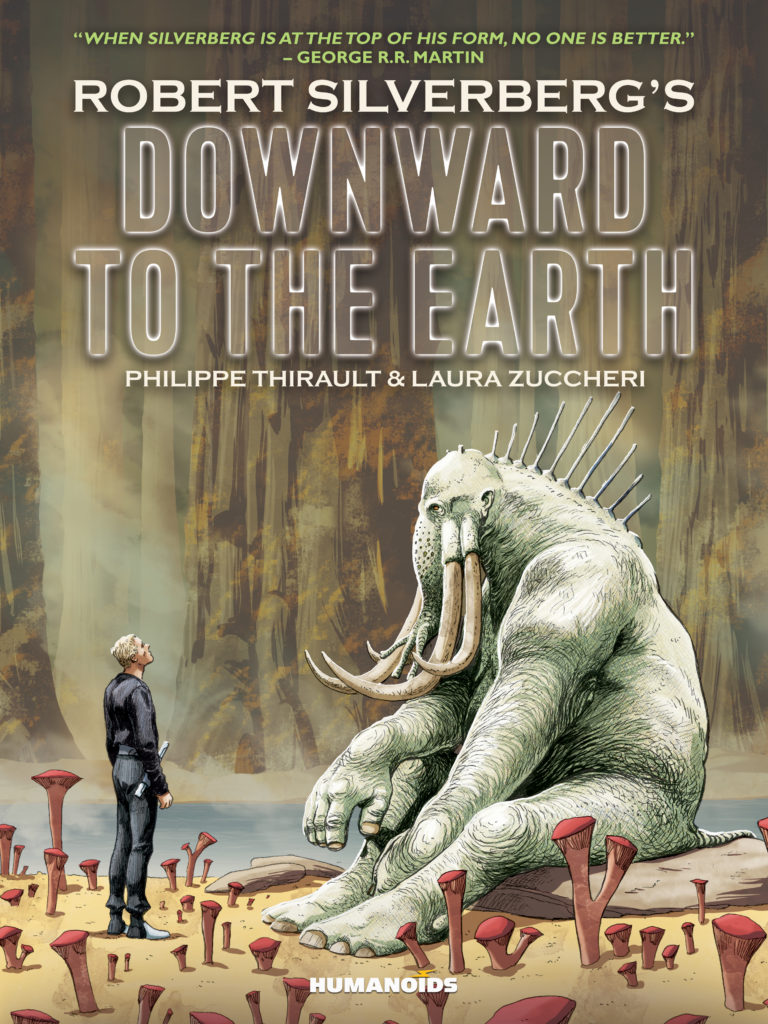

Robert: I don’t think so. A lot of my best science fiction crosses over into mainstream fiction (DYING INSIDE, for example, or BOOK OF SKULLS), but there is always a science-fiction element lurking somewhere in it (telepathy in one, immortality in the other). DOWNWARD TO THE EARTH, all about aliens and group minds and extraterrestrial life, is certainly science fiction, but Joseph Conrad used much of that book’s other themes a century and a quarter ago in “Heart of Darkness,” and nobody thinks of it as s-f. I don’t know whether I would have had the same success if I had set out to be a straight mainstream writer. It never occurred to me to try.

Jud: I’ve interviewed many genre writers who surprise me with their fiction recommendations for their readership. Crime Noir masters recommending Charles Dickens and masters of the horror genre recommending Peter Pan. Much has been discussed about Downward to the Earth being an homage in some way to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Was his work inspirational to you?

Robert: It certainly was inspirational to me, as I make clear by borrowing one of that story’s most important characters to be a prominent figure in my own. In 1968 I visited Kenya, where I learned about colonialism (and elephants), and “Heart of Darkness” had had a powerful impact on me ever since I discovered it when I was about sixteen. And the following year it was an obvious next move to translate the Conrad novella into a science-fiction novel by setting my colonialized region on another planet and making the elephants into considerably different but still elephantine creatures.

Jud: Should young writers look to his work in the same way they look to other science fiction authors?

Robert: Every young writer should know the work of Conrad, one of the most important writers of the early twentieth century. He should know Joseph Campbell, too — I drew on his thinking as I was constructing LORD VALENTINE’S CASTLE — but neither one of them was a science-fiction author, of course.

Jud: Even more importantly, if you could choose a reading direction for young, budding science fiction writers to find inspiration, where would you send them?

Robert: Everywhere. They should read everything they could — a lot of science fiction, of course, but also all of the classics of world literature, and as much scientific material as they can absorb. It all will be of use eventually.

Jud: With this graphic novel adaptation, Philippe Thirault (writer) and Laura Zucchini (art) had to distill 250 pages of your novel into a 108 page sequential art format. John Irving talked about adapting his novel “Cider House Rules” for film and how he had to distill the emotion and breadth of his book into essentially a one chapter story for the screen. But he also said that it stood on its own apart from the book (and won the Academy Award for best screenplay). I’d like to think people reading this adaptation would be inspired to run out and read the novel. The one without pictures!

Maybe that’s what adaptation into other forms might be useful for? Not so much replacement as inspiration to go back to the source material?

Robert: I think they did a brilliant job. They used the underlying concepts of my novel to create something that is powerful in its own right. I don’t think that the purpose of graphic novels is to send people back to the source material, but I certainly hope that it happens.

Jud: Surprisingly, there have been very few adaptations of your work into television, film and comic book form. Is this by choice? Are you protective of your work and how it’s presented to the public?

Robert: Not at all. I give the adapters free rein — my book is my book, their graphic novel or film is their graphic novel or film, and they are independent entities, I don’t interfere in the adaptations. That there have been so few movie or TV adaptations of my work is an artifact of the weird way those industries work, and I have no control over that. There has not been a time in the past fifty years when some novel or story of mine has not been under option for a film or TV show — six of them are under option right now, including DOWNWARD TO THE EARTH — but though several of them have come right up to the brink of production, only a couple of them have actually made it to the screen. It’s frustrating, but there’s nothing I can do about it. I cash the option checks and hope that something will eventually happen with the project, but usually there is some upheaval among the studio executives, everything in the works gets canceled, and that is that.

Jud: I know you’ve mostly stopped writing on a regular basis and you’re enjoying a well-earned retirement with your wife and your garden.

But…are there moments when you’re watering the flowers or strolling in your neighborhood or just sitting and re-reading a favorite classic that you daydream about a story left untold? Maybe the seed of an idea that might still be planted? I find it hard to believe that a man who has spent almost every moment of his adult life bringing fantastical ideas to the page just stops having stories to tell.

Robert: I’m 83 years old and have written enough to fill whole bookcases with my work. Writing is hard work and at my age I don’t want to go on with it. As you say, I’d rather be watering the garden, or strolling around in my neighborhood (or in London, or Paris, or Rome), or sitting on the porch re-reading some beloved book. I do still get story ideas, of course, and now and then I even make a note of them, but it ends there. I doubt that I will ever write more fiction. Very few writers my age have stayed with it into their eighties, and very few of those have produced anything worthwhile at an advanced age. (Very few have even lived that long.) The mental machinery still works, but the will to put it into action is no longer there. I have no regrets whatever about that, since most of my work is still in print and people still read it (and adapt it into other forms!) If I were altogether forgotten, I might be motivated to get some new material out there before the public, but that’s not the case. I’m enjoying my retirement.

Comments are closed.