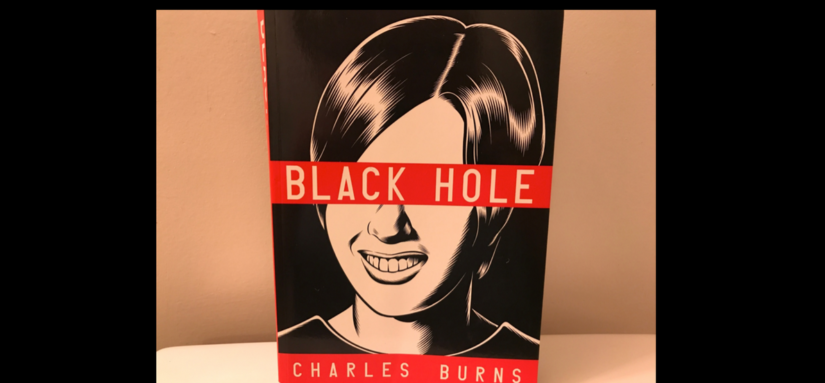

Black Hole by Charles Burns is a book I’ve been meaning to read for about as long as I’ve been steadily reading comics. Its cover is striking, presenting next to no information to the reader but still creating an anxious mood with the simple image of a high schooler forcing an uncomfortable smile for a yearbook photo. Their eyes are blocked by a strip of red across the image for the title. When I picked up Black Hole, I had no idea what it was about. I didn’t even know it was horror.

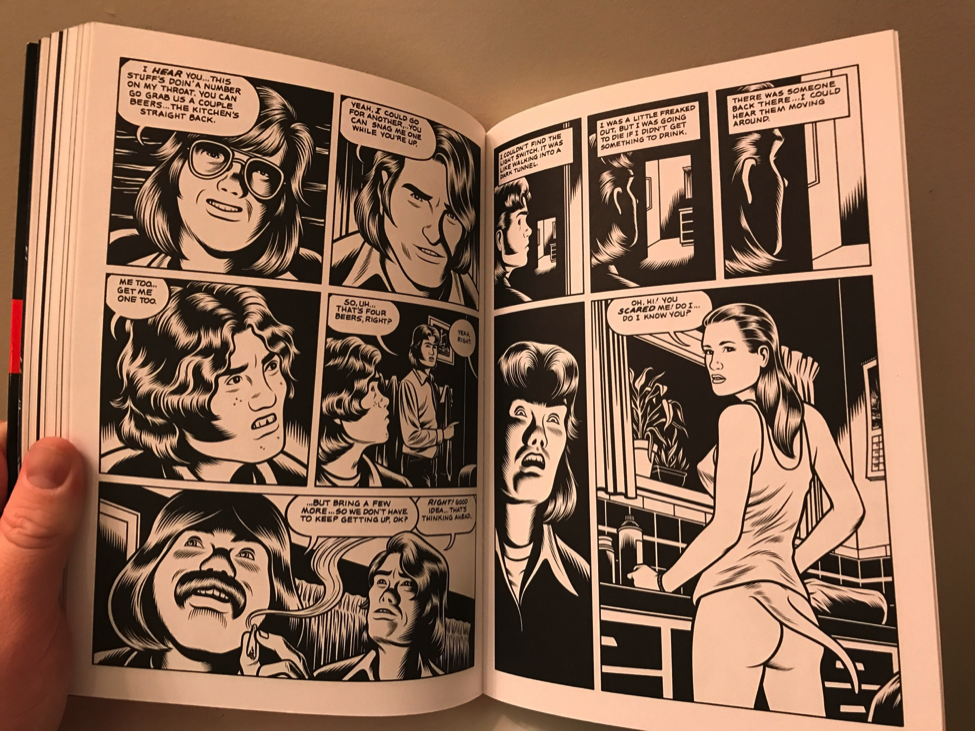

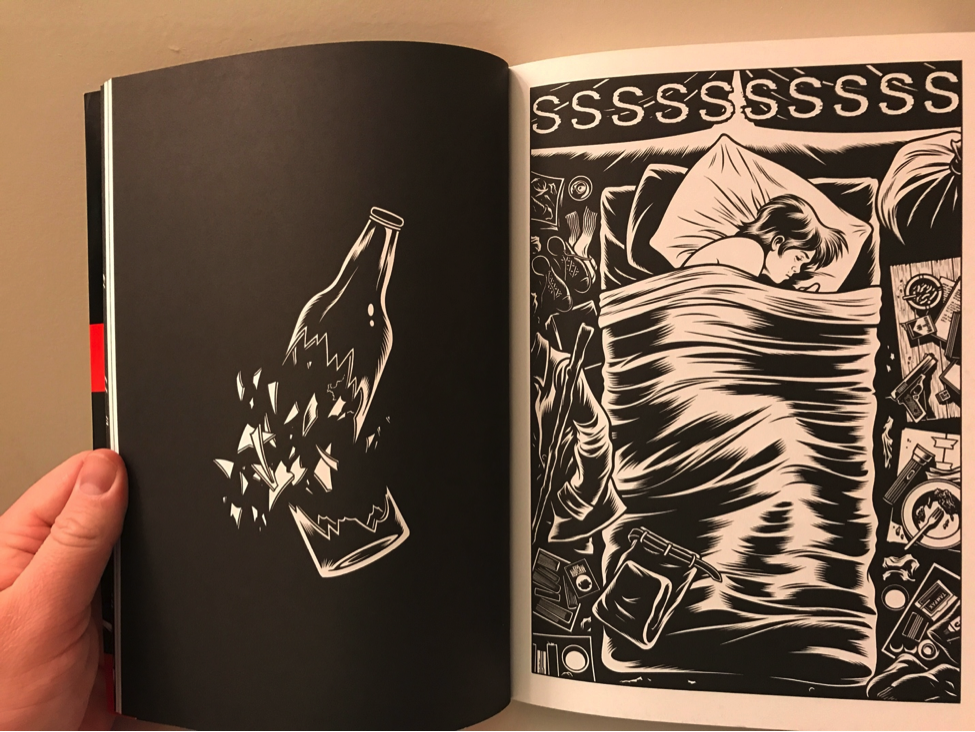

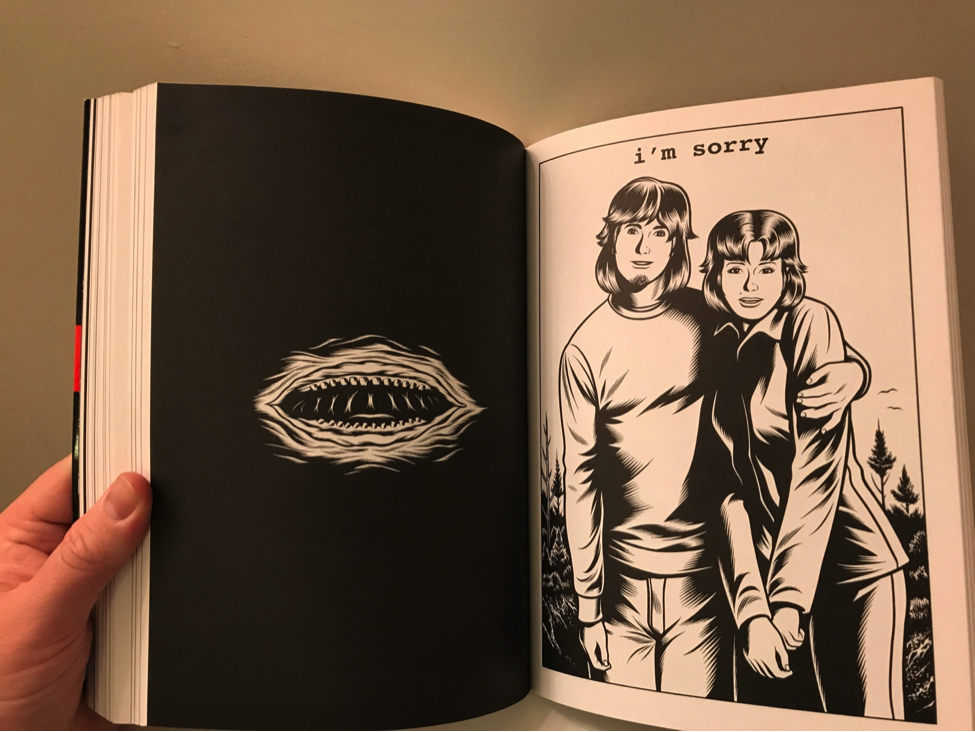

I did know, though, from the evocative front cover, that it would be beautifully illustrated from start to finish. In shape, thickness, and format, flipping through it reminded me of one of my favorites – Craig Thompson’s Blanket. The art style was markedly different, making use of black and negative space in a way I’ve never seen another artist, in comics or otherwise, do… but it was still that “Oh, this might be like Blankets” that made me pick it up. Now that I’ve read it, I have to look back and laugh. Black Hole ain’t Blankets – but then, I don’t know if I know of any graphic novel that feels like this. Let’s break it down.

Black Hole is about a “bug” – basically, an STD – that is going around Seattle in the 1970s. Or, maybe it’s a nation- or worldwide thing. We never find out. We never find out much about the bug, except that it’s common knowledge and it physically mutates people who have it in different ways. One character sheds her skin like a snake, another has a tail, another has little tendrils coming out of his ribs – all stuff one can hide. Then, there are other afflictions that turn those who carry the virus, called “sick kids” by their peers, into social outcasts. Some of them look like they’re wearing B-movie masks, while others develop dog-like jowls. These sick kids separate themselves from society and live in the forest for the most part. The story loosely follows two newly infected high school students, while also focusing on a mysterious killer who is picking off the sick kids. The murder plot takes a backseat to the coming-of-age drama that feels, sometimes, like a colder version of Freaks and Geeks that delves less into the social hierarchy of high school and more into the overlap between adolescent sexual awakening and 70s drug culture.

Now, when I say “cold,” I’m not saying that Black Hole is emotionless. It’s not, at all. I found myself invested at the end of the book, sad to be leaving some of the characters behind. Black Hole is colder than most coming-of-age stories because there is no resolution for anyone, no real sense of watching characters find themselves in the midst of adversity. Instead, we spend time with these characters, living life with them, and then, in the end, we leave. Some of them go on, some don’t. We don’t get the sense that they’re going to be okay, or that they’re not. We don’t get the sense that they’ve learned some big lesson. They’ve lost, they’ve fled, they’ve suffered, they’ve found momentary peace, they’ve taken a baby-step toward moving past trauma… but the lack of a neat bow on their stories doesn’t mean Black Hole feels incomplete.

At first, I admit, I struggled with telling the characters apart. It’s that 70s hair! The two main characters – Keith and Chris – look very much alike for the first few chapters. All of Keith’s friends look pretty similar to him, especially their haircuts. Chris’s boyfriend looks, in some panels, identical to her. It’s a problem in the first two chapters or so, but it works itself out. Keith’s friends are relegated to bit roles and he gets a haircut, and Burns uses small but striking details to set the characters apart. Once I was into the story and knew who I was following, the struggle was gone – but I say this as a warning to those who are planning to read this. If you feel as I did after the first chapter, don’t worry. Keep reading, and you’ll understand very, very shortly. It was published over the course of ten years, so of course Burns’ style evolved, but I think much of it was a purposeful and accurate depiction of Seattle in the 70s. There’s even a comment that hangs a hat on it after Keith gets a haircut.

Black Hole goes back and forth between Keith’s story and Chris’s, which overlap… slightly. Mostly, these are two distinct stories that pay off in a way I could have never expected. There’s a lot to be said about Burns’ plotting, which resists structure while still feeling one-hundred percent satisfying. It feels focused on character without ever being something I’d called character-driven. If that sounds strange, you’re right – it’s utterly unique. It’s structured in a way that we find out important information from characters after it happens, through their reflections or conversations with minor characters. It’s also not plot-driven, because the events in the town are treated as secondary to the characters who stumble through their lives as Burns’ story unfolds. Instead, Black Hole is idea-driven. We see glimpses of life through Keith and Chris’s experience that build into a statement – or, rather, a question – by Charles Burns about what it’s like to be different, to need human connection, and to feel the desire to run away from childhood and never look back.

NEXT TIME: We sink our fangs into American Vampire author Scott Snyder and artist Sean Murphy’s acclaimed Vertigo-series, The Wake.

Comments are closed.