All this month, we’ll be helping Children’s Hospital Los Angeles‘ Make March Matter campaign, which aims to raise over a million dollars in March alone for CHLA through the efforts of its corporate partners, among which we are proud to be numbered. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles sees over 528,000 patient visits annually, and is the top ranked pediatric hospital in California by US News & World Report. You can help Make March Matter by simply attending one of the many events or participating in one of the many initiatives being offered by CHLA’s partners (including our event on Saturday, March 25), all listed at www.makemarchmatter.org.

To help remind us all to Make March Matter to support children’s health, we’ve asked all our contributors here at the website to focus on books and comics for kids, or the books or comics that meant the most to them as kids, because we firmly believe that escaping into literature is just as important in keeping children healthy and happy.

Today’s piece is from novelist Adam Korenman:

Middle school is a tough time for kids. You’re too young to understand much of the world, let alone your place inside. You’ve started to sense a sexual preference, but you can’t possibly fathom what that will mean. And math. Goddamn it, math. Just being there, in your textbooks, mocking you.

For a young, shorter-than-average Jewish boy, middle school really sucked. I lived in Fort Worth, Texas, in a comfortable suburb that was more rural than urban. I went to a school with all of my friends, did well in classes, and felt in control of my life (as much as any third grader can). But then Fourth Grade arrived, and with it, chaos.

My parents wanted me to get the best education possible. In their eyes, the slapdash curriculum at my current school simply wouldn’t cut it. My brother had been in the public system his entire life, and they thought that he, my sister and I deserved something even better. They also wanted a strong Jewish education for each of us. And so, in my fourth grade year, I was pulled from my comfortable life in Fort Worth and transported daily to Akiba Academy of Dallas.

For those of you not well-versed in the geography of the Lone Star State, this was a 50-mile journey, or 100-mile round trip, if you want to get fancy. Given the traffic situation, this meant two hours in the morning, and about one-and-a-half in the afternoon. I was having so much trouble staying awake in class, I asked my mother if I could have coffee. Thus began my addiction to caffeine, and the end to my hopes of seeing 5’8’’.

In the four years I spent in private school, I went through a series of increasingly exhausting adventures. I had trouble making friends, and the teachers seemed out to get me. The only way I was able to cope with the incredible stress, the only escape I could find at all, was books. I read voraciously, devouring a few novels a week (kid novels, I wasn’t reading Anna Karenina). My favorite series, and the one that resonated the most, was the Sideways Stories from Wayside School.

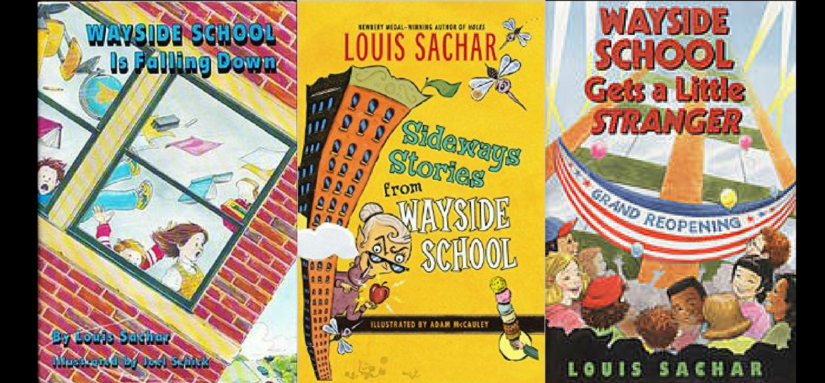

Written by Louis Sachar of Holes fame, the five-book series of the Wayside School children proved a suitable salve for my adolescent mind. The kids there were just as stressed, just as lost as I felt. They dealt with insane teachers, magical misadventures, and maybe just a little arithmetic on the side. They have a teacher that turns bad kids into apples, a mysterious floor that appears and disappears on a whim, and a curriculum that veers wildly off course from the School District’s recommendations. All of this is because, like Pratchett’s Discworld, the school itself is an absurd creation: A thirty-room building built thirty stories high.

The book, and the ensuing series, was written as a collection of short stories that loosely wove together a cohesive narrative. Each chapter focused on one of the many students in Ms. Jewel’s class on the thirtieth floor. Sometimes they would be playful lessons in math, other times it would be a covert analysis of sexual harassment (pulling pigtails), and sometimes it was just a good joke played out as a story.

I needed the absurdism of Sachar’s books. Like Shel Silverstein, he looked at the world through an obscure and foggy portal. He tapped into the undeniable weirdness that is middle school, and let it play out through fantastical stories. There was the time a young girl in an overcoat fell out the window on the thirtieth floor. The PE Teacher, Louis, sprinted across the yard and caught her just in time. There’s the new kid, who turns out to be a dead rat wrapped in far too many raincoats.

But the final story in the original book resonated the most, and really cemented my love of both the author and the series. In the last chapter, the students are unable to go to recess due to a blizzard. The PE teacher, Louis, comes inside to tell the kids a story to pass the time. He regales them with tales of other children in other, normal schools. The banality of life in comparison to their absurd adventures seems, to them, comically weird.

It was as though a lightbulb went off in my head. Of course, Sachar wasn’t reaching out with his words directly to me. He had created a collection of stories that resonated with most children ages 7-15. He had tapped into the unmistakable frustrations that every middle schooler endures. But for me, the series was more than just an escape. It was a reflection of thoughts I had yet to put to words. I felt lost, unrecognized, and alone. Like the kids in Wayside, I looked out and saw a world in which I did not belong. But then, during a wintery recess, I saw something else: Everyone out in that world was just as confused.

That was the true genius of Sachar, and indeed of most absurdist writing. Using a mockery of reality, authors are able to remove the fear of the outside. Suddenly, adults don’t seem so omniscient. Teachers can be people as well as educators. And school, no matter how restrictive or confounding, can still retain a little bit of fun.

So, from one weird kid to another, thank you, Louis. Your books may not have been as satisfying as your time in the sweater factory, but they helped at least one lost boy find his way.

Comments are closed.