This past October, I posted “Why comics?” on my social media accounts. I kept it vague, because I wanted answers from everyone. Folks who write them, draw them, read them, put them in between slabs and mount them on a wall. I wanted to know why, of all media, of all artforms, why comics had caught their fancy. One of my favorite answers was from El Anderson (@FemmesinFridges on Twitter), who said, “Because it is one of the last artforms which hasn’t explored 1/10th its full potential yet.” (As an aside, Kieron Gillen, who I believe to be one of the writers who has pushed the boundaries of comics most in modern times, playing with the form of the medium, deconstructing, and reconstructing in wholly new ways, seconded El’s assertion.) I, too, agree with that – that the boundless and unknown opportunity for new discovery in this medium is the most fascinating thing about it, and that the books that try to do something entirely new are the most fascinating stories within it. I thought back to that answer about the exploration of comics’ full potential when I read Jeff Lemire’s Trillium, a sci-fi love story/war epic (kind of) that engaged me in ways I’ve never experienced before.

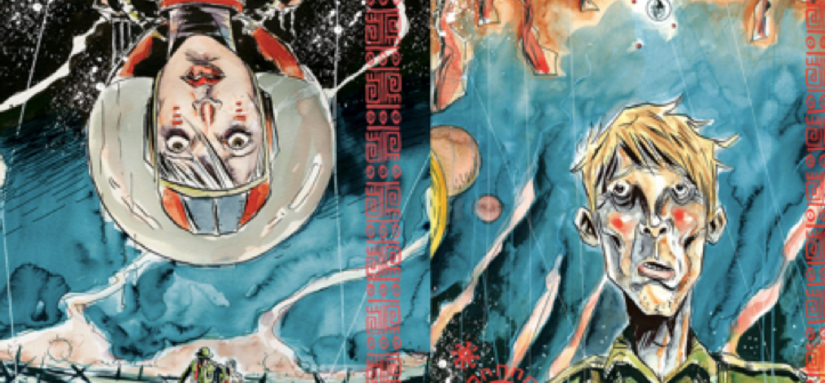

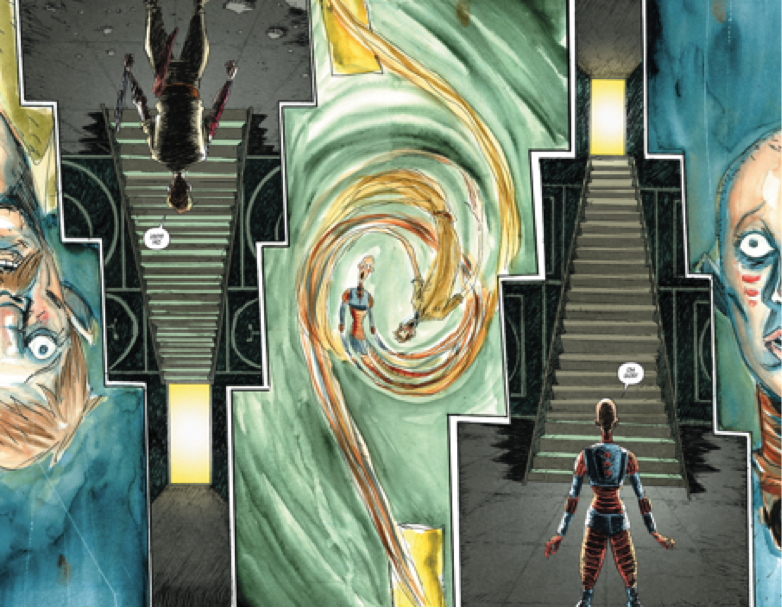

Considering the plot, Trillium is not something I’d suspect from Lemire. Jeff Lemire’s work has been made up of long-form, character-driven stories grounded firmly in reality. Even Sweet Tooth, which stars a boy with antlers, was as realistic as any comic book I’ve ever read. Lemire handles sci-fi with that same touch, though, grounding this tale about time travel firmly within its two lead characters – Nika Temsmith, a scientist from the year 3797, and William Pike, a former soldier and explorer from 1921. These stories overlap, first in a way that I expected, and then… in a way that left me stunned. Halfway through Trillium, I found myself immersed, physically moving the book as I read, flipping back, turning it upside down, and then, in the conclusion to the sixth chapter, turning the book in a spiral as I read each panel.

Here’s the thing. To pull off this kind of work, two things have to happen. 1) There has to be a reason within the story. Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing did this well, and Scott Snyder’s Batman had a pretty interesting story-based reason for a similar tactic in recent years. Then, on the other hand, I’ve read comics where suddenly, for no reason, a page or even a chapter switched to horizontal calendar style. Those single baseless switches are jarring, while, with Trillium, I didn’t even pause to read before I moved with the book. Which brings me to 2) The narrative has to be so immersive that readers aren’t more conscious of the fact that they are reading than the narrative. All of this would be very post-modern if Jeff Lemire’s intention was to break the reader out of the story and remind them that they’re controlling the way they read Trillium – but that isn’t the effect of the way he ensnares the reader. Instead, I found myself tumbling through Lemire’s two worlds as I turned the book, almost as if I was steering a ship through them, not so much controlling as I was falling.

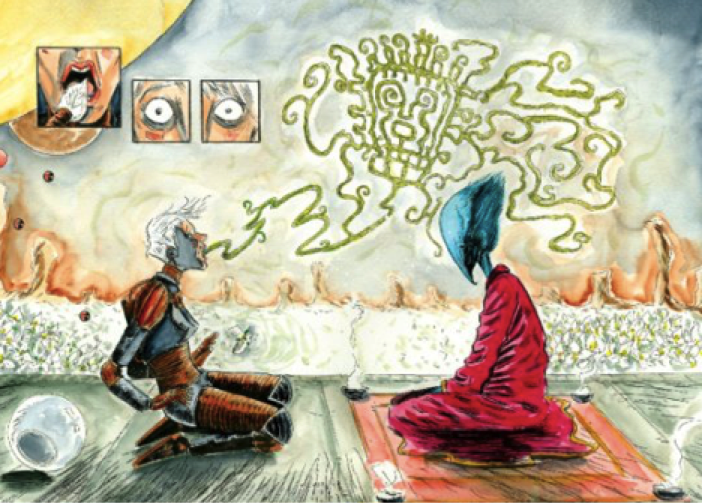

The entire comic doesn’t force the reader to reorient themselves over and over. That part is limited to a few well-earned sections, but the rest is a beautiful story about the pain of being alone, and the beauty of realizing that sometimes, if you open your eyes and look really hard, you might not be alone after all. I wrote a lot about the way Jeff Lemire broke from the norm, using character-driven techniques to make me physically find the path through this book, and as amazing as I found that to be, maybe the biggest way that Lemire uncovers some of that depthless, untapped potential in this artform is by telling a story that, with or without the creative formatting, makes us feel deeply.

Comments are closed.