Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko are the comic-book artists best known for “other” worlds. But where Steve Ditko’s “other” was strange (pun intended), Kirby’s was overwhelming. Ditko’s Eternity was ethereal, literally a doorway in humanoid form. By contrast, Kirby’s Galactus is overwhelming, almost a burden on the page.

But Kirby had a polar opposite to his “other” and that was the notion of “The Kid.” Kirby worked on four iterations of this least of superheroes and this weakest of sidekicks. The first of these was the original, Bucky.

Kirby didn’t create Bucky, The Kid was included in Simon’s first studies of Captain America. But some things are noticeable: he barely has a costume. He wears a fencing shirt, gauntlets, trunks, leggings, pirate boots and a domino mask. The costume has two colors (plus black for the mask), red and blue. Sometimes the trunks and boots are blue and the leggings are red. But other times the trunks and boots are red and the leggings blue. This inconsistency would affect most versions.

Bucky is the first of four versions of The Kid we will look at here. He has no super powers. He doesn’t have an impenetrable shield and, until recent stories, doesn’t pick up a gun. This is kind of incredible when you consider that Bucky is in the middle of World War II. Facing the Nazi Germans or the Imperial Japanese. He is basically an unarmed civilian.

The backstory doesn’t get any better. His father died in army training. Not exactly a hero’s farewell, there. When his father dies the army camp adopts him – somehow. I’m not sure what paperwork that involves. At the time no other relatives were mentioned, but in the ’70s his mother, sister, and other relatives were sketched into the story.

At the start of his story, Bucky is fifteen. In World War II that wasn’t three years til majority, it’s six years away. In real life you didn’t become an adult until you were 21. But for whatever reason, Bucky, apparently the son of the only accidental death during training, is adopted by an army camp.

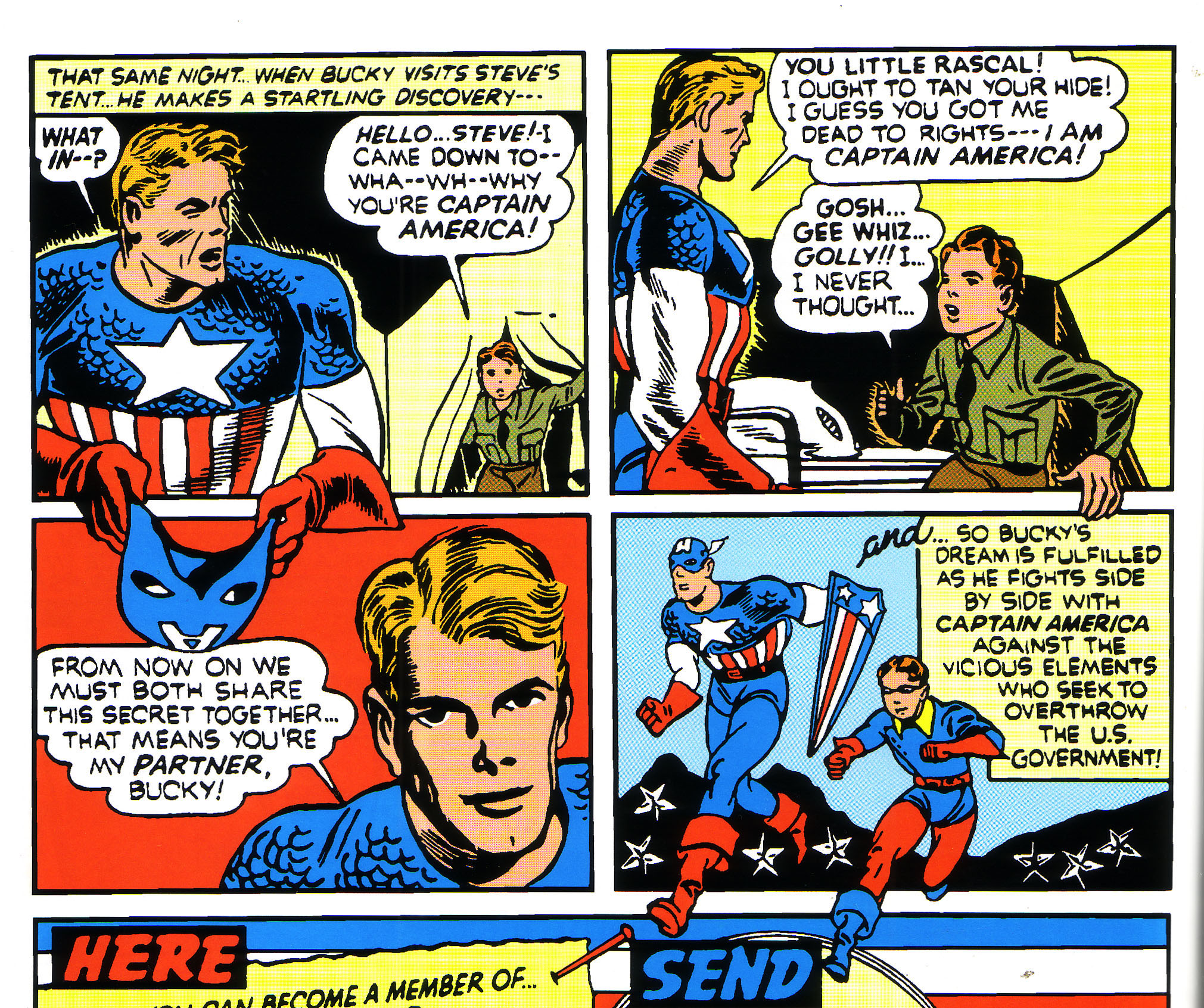

By pure unbelievable coincidence, Bucky becomes close friends with Steve Rogers, the clumsiest soldier to ever not get killed in training. Entering into Rogers’s tent unannounced, Bucky discovers his friend dressing in his Captain America costume. There is no explanation why Private Steve Rogers gets his own private tent. There is no explanation how he goes from his tent to wherever he would do his daring and back again without being noticed. He was in a bright red-white-and-blue: how bad were American sentries?

But Captain America does not kill The Kid, or beat him into a non-communicative other-abled person through enhanced interrogation techniques, as one might think he would do now. Captain America also does not go to higher-ups. He does not refer to precedent, legislation, policy, or instructions. Which maybe is just as well because he puts The Kid in a costume and a mask and sends him straight at Nazis.

Sure, Bucky wears a mask but he’s called Bucky. Nobody in their division notices Captain America is always nearby. They don’t notice that Bucky has the same name as The Kid they adopted, and dark hair like The Kid they adopted, and is always near wherever they happen to be.

The story’s been pulled to pieces a thousand times. But if you think a widely popular story is simply stupid, you’ve probably missed something. In this case, Captain America and Bucky were selling a million copies a month. Somebody liked it. So let’s look at the story through the eyes of the time. Let’s see what Simon and Kirby were actually saying.

When people were orphaned they often had to find employment. Welfare didn’t exist, yet. So fifteen-year-old orphans had to do things like join the circus or the army. The opera Daughter of the Regiment is also based on an army unit adopting a child. A fifteen-year-old among soldiers would have been common a war or two before these stories told. How many times have you heard the story of someone who lied about their age to enlist? Do you think they were all believed?

Stories often maintain the previous generation’s experience. So wrestling gave us large families long after that had largely ceased to be. The four Graham brothers were unrelated. The three Anderson brothers were not related and Ric Flair was not their cousin. There are still more lifelong friends in television and movies than still exist in real life.

Steve Rogers got into costume and made his way in places without CCTV and lots of lights. It was a much more open world. Open lots still existed because not every lot had a house built on it. Large open spaces existed, too, like areas which hadn’t been built up, yet. Kind of like Detroit, but going up rather than down. People went about unwatched. So it was reasonable in a story that someone would put on a costume and manage to get somewhere.

In the same way, people didn’t all have to check with somebody else. Decisions were made on the spot. Slews of legislation didn’t exist yet: local managers controlled who they hired and fired. They could use success as a justification for their actions, as opposed to now when following the rules is more important than succeeding.

And above all else, there were large numbers of people who could see themselves in the story, and it was they whom Kirby was addressing. There were the younger brothers of soldiers, who wished they could help but were a little bit too young. But they saw The Kid adopted by the regiment and that gave them a vicarious belief they might be there.

It was an American story. It wouldn’t have worked in Australia, where kids literally went hungry for the war effort. It wouldn’t have worked in Britain, where children were moved so they weren’t bombed.

Soldiers swept up into the war saw The Kid and felt like him. There was a mass draft, thousands of men felt like The Kid, lacking the skills and trying to learn. They wanted to be as good as others and were anxious for higher-ups to tell them they were doing it right. And in the military they often felt they had found a family. World War II was an intense experience, far more intense than any “intense weekend experience” they sell you. It lasted four and a half years for Americans and it defined the people who lived through it for the rest of their lives.

Jack Kirby did the bulk of the artwork for this run, excluding what he couldn’t do while fighting in Europe. He made The Kid just a little gangly, slightly naïve (“I suppose our next stop will be in the dragon’s tummy”) but always in the mix. He is the doorway for his own readers, proxy for the brothers in arms and the brothers at home. And he continues that way until 1949, when Timely gave up superheroes.

But another version of The Kid was elsewhere. Sandy The Golden Boy debuted as the sidekick of the Sandman in December 1941, just nine months after Bucky appeared.

Sandy was created by Mort Weisinger and Paul Norris. Jack Kirby would later rewrite the origin of one of Weisinger’s characters, the Green Arrow. It was something Mort Weisinger resented for years. If so, Sandy The Golden Boy sheds interesting light on that.

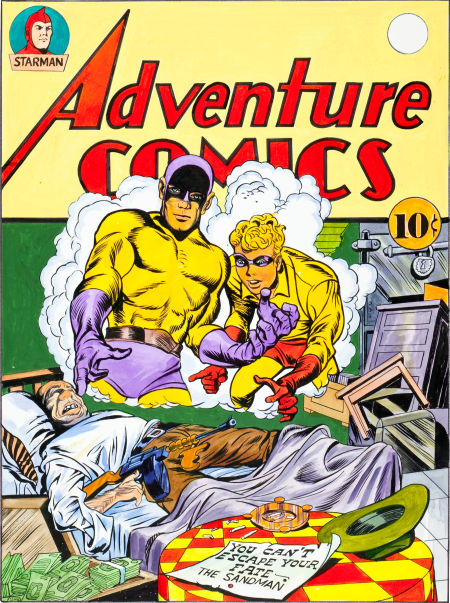

Sandy was cut from the Bucky mold. He wears a yellow shirt with a red collar. The shirt matches his leggings; the collar matches his gloves, boots, and trunks. The domino mask, which in modern renditions is colored red, is usually black. The costume is a variation on a theme, and so is the backstory.

The Sandman started out as a mystery man, wearing a colorful gasmask, a green suit and a purple cape. The Sandman puts criminals to sleep with an anesthetic that smells like lilacs and is sprayed from a gun. He also spreads sand at the scene. The sand and lilacs are his calling card.

But when mystery men became less popular the Sandman was converted. He was put into a purple and yellow costume and given a sidekick. He was in fact given everything that was the rage at the moment.

His sidekick is an orphan, just like Bucky, and he is Sandy The Golden Boy, because “The Boy Wonder” was already taken. However, though his parents are dead, his aunt is alive and she is Sandman’s girlfriend, Dian Belmont. It may seem strange for a non-relative to take a child as a ward when his aunt is available, but if Dian Belmont adopted him she would have become a single mother.

There was a big stigma against single mothers who were not sexless widows, and that included in fiction. Dian Belmont, the girlfriend of Wesley Dodds, would have been too feminine an influence for someone like Sandy The Golden Boy who was learning to be a hero. So she disappeared, later it was retconned that she died, but at the time she just vanished into thin air.

Besides, fiction at the time was filled with orphans – look at Shirley Temple movies – they needed Sandy to be the orphan who came out all right. No one’s ever analyzed this fictional need as a social phenomenon, but given what’s come out about how kids were treated in orphanages and other institutions at the time, it seems kind of obvious.

Like Bucky, Sandy was The Kid but he was a bizarre form of the model. In the comic there is a Sandman who in real life catches criminals. In that real life, there is an orphan named Sanderson Hawkins who reads a comic book about a hero named Sandman. In real life, Sandman wears a green suit and a gasmask. In the comic he wears a purple and yellow costume. In the comic his sidekick, Sandy, wears a red and yellow costume. Sandy looks like Sanderson in Sanderson’s opinion, so Sanderson sews a suit to match Sandy’s. By coincidence, he assists the real Sandman on a case, and Sandman takes orphan Sanderson on as his ward.

I suppose it’s still family, because Sandman’s girlfriend is Sanderson’s aunt. But from our point of view, it’s a de facto relationship. Perhaps it was back then, too.

Sandman in real life decides that Sandman in the comic has the right idea. The war means people need a visible symbol and the visible symbol he decides on is the one he steals from a comic book. So Sandman and Sandy go to war.

Sort of. When Simon and Kirby got hold of the title they took the Sandman back into the realm of dreams. Sandman and Sandy haunt the dreams of evildoers, something not far off what Simon and Kirby would do with their ’70s version of the Sandman. They also chase villains in this world, using a harpoon gun to give them a line to swing on.

Kirby connects this version of The Kid to his “other.” But I don’t think it works, in as much as he tags along, but is not part of the otherness nor does he really defend this world. It doesn’t fit the mold. This is shown not when superheroes lost popularity but when they regained it, which we’ll explore next time.

Comments are closed.