We stand upon the earth, the gods are above us, the demons are below us. That is pretty much as close as you can get to the common basic theology of humankind. Of course the gods are usually bright and the demons are usually dark, but not always.

In comic books, the same rules apply, even at Christmas. Superman is bright and (almost) all-powerful, and his Christmas stories are about the pity he has for others who aren’t doing so well. Batman is dark and deals with even darker things who might harm Christmas. If he faces the brighter side of the holidays it’s because somebody else, like Robin, forcibly brings it to his attention as he did in the Batman the Animated Series episode “Christmas with the Joker.”

So what about Hellboy? He comes from a different mold. Hellboy doesn’t just deal with those demons, he’s one of them. He lives in a world in which different laws of physics actually fight it out. Hellboy’s job is often to get to that place of other physics and not negotiate. But even for Hellboy, in this world, Christmas comes around with all the danger and menace that implies. It’s like those Christmas commercials where the mother and her children are living in the car and one of the kids asks if Santa Claus will find them.

Check out http://www.darkhorse.com/Features/Animations/10/Hellboy-A-Christmas-Underground and pick up “Hellboy’s Christmas Underground: for free. It’s not strictly a comic, but a comic that is enhanced by just a little bit of animation.

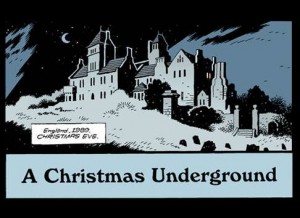

It’s Christmas Eve and Hellboy is at an English manor, working. He’s like the cop still on the beat, the oncologist talking to a patient who won’t make it through Christmas, the demon who visits a woman whose life is plagued by demons.

This story is mostly in black and white, with the occasional color to highlight, a little bit like the movie Sin City. The backgrounds, too, are mostly spare. It is a story in which the world is made by our actions, not that the world makes us who we are. It is the people (and other sentient things) and what they have done who are the core of the story. And it begins with a stark, lonely old mansion and Christmas Eve.

We have an opening scene of the house under the stars, then of the stone walls of the stone staircase. We are already underground, if we can but see it.

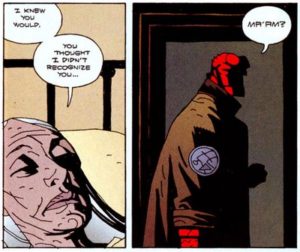

Hellboy knows the stakes. He’s told right at the beginning she won’t live through the night. It’s a case of short-term palliative care.

The doctor says she has lost too much blood, which is an odd diagnosis. Did transfusions not exist in 1989? Is there a wound here? Conversation seems to indicate she is old and exhausted, not wounded. Hellboy sends the doctor home.

The priest quickly fills in Hellboy, and us. Mrs Hatch lost her daughter; the girl went into the graveyard where there were stones older than any Christian grave. He doesn’t say whether those stones are older than any other grave in the yard or older than any Christian grave anywhere. In the end, that matters little. The age of the stones marks this as a place of power.

Power corrupts. It even corrupts those who do not wield it.

The family died one by one and now Mrs Hatch is all that’s left. Except Annie Hatch, who is alive and in a graveyard. This life-amidst-death versus death-amidst-life is a theme throughout the story, and it’s well done. One good thing about Hellboy stories is they do not shirk from the tough stuff.

Hellboy goes to speak to Mrs Hatch. He promises to give her daughter, Annie Hatch, something in a small box.

Hellboy gives the priest a list of things to do. Then he goes into the graveyard where a rat tells him, “beware.”

Hellboy overturns ancient stones and enters the void this reveals. It is not just a hole. But then, Hellboy often goes through a small portal to find a large, underground place. Hellboy confronts an impossibly large stone wall, which is seriously decorated with carvings and a bust which repeats the rat’s warning, “beware.”

It’s worth mentioning that there is a strong stream of symbolism in this story. It’s not the cheap symbolism where people look at complex glyphs or give rhyming prophesies that never make sense at the time. The symbolism comes from the roles people (and other things) play and the things people (and other things) do.

Was the symbolism just an accident? I don’t think so. Can I prove it’s really there? I think so. Remember the rat and the bust. They have no role in the story except symbolism. It’s why each only appears once and each appears to foreshadow its like. In other words, look for the second rat and the same face.

If it were anyone other than Hellboy, they might listen to the rat or the wall. But he follows a floating candelabra and meets Annie Hatch, the missing girl, now a woman.

In that other world there are many people who walk amidst flowers and flowers in large stone pots, pillars that hold up arches, flowing curtains, and flying doves. In a subtle touch, Hellboy and Annie have very different views of how far away the house is from the grave.

The distance is not just physical. The different realities are in themselves a kind of distance. Annie describes the mansion as a terrible, cold house, as if there was such a thing as a warm grave. But, again, distance is a substitute for an emotional state.

As that conversation fills in background, the tone of the story becomes more surreal. Others join Hellboy and Annie for a formal dinner. It is Hellboy who grounds everything, he pierces the insanity. Tying together several plot threads, Hellboy (partly by accident) strips the veneer of politeness from the dinner party.

Like the late Victorian era, the manners that had once guided discourse have become an all-consuming pretense. When the pretense is removed all that is left is self-serving savagery. Hellboy battles the guests at the dinner, who no longer even look human. The hall in which they fight has also been stripped of its veneer. And then Annie’s husband shows up and it’s on.

Conflict explodes into conflagration. And in the cold stone mansion, the priest who had proved so useless in Mrs. Hatch’s life is now conducting an exorcism. He quotes I Peter 4:5-6, in which God is the judge of the quick and the dead. This is an ol- fashioned expression, the quick being the living, and the first kick of a baby in the womb is the quickening. It does not refer, as many people believe, to those fast enough to get away and those too slow, and hence captured and killed. The phrase “quick and the dead” occurs four times in the King James Bible (the reference to judge identifies which instance is quoted here), but has been increasingly edited out of more recent translations.

It also reminds us of the distinction of the living and the dead. Of Mrs. Hatch, who is going to die, and Annie Hatch, who may as well have.

The threads laid down at the beginning of the story are tied up one after another. Annie and her mother meet the priest … and Hellboy and the demon have a mutual meeting over Christmas. Death is the inevitable result.

This is not a story of Christmas making everything all right. It is not a story to remind us to have sympathy for the less fortunate. It is a story of active evil, which has been allowed to fester for years. That always has consequences. It’s time for everyone to die. Happy Christmas and Merry New Year, Hellboy style.

Comments are closed.