Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions

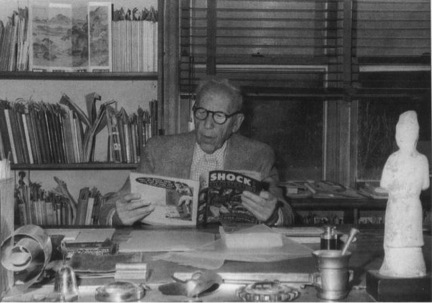

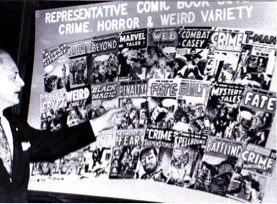

While other publishers provided testimony during the Senate hearings, the two central figures in the debate were Wertham and Gaines. Wertham, a respected psychiatrist, had impressive credentials, and he was seen as an expert in the field of comics and juvenile delinquency.

Gaines, by contrast, was the most outspoken of the four publishers who testified, but he did himself no favors during the hearings. Gaines’ testimony, scheduled for the morning, was delayed until the late afternoon, after Wertham got a chance to make his case, and the publisher suffered for it. Gaines’ biographer stated that Gaines was taking diet pills, and by the late afternoon, the medication caused fatigue that affected his testimony. Whatever the cause, the result was that Gaines’ matter-of-fact denials about questions of poor taste in comics fell flat. Gaines repeatedly stated that he thought comics were harmless entertainment, not necessarily good for kids but not harmful, either.

Gaines was publicly lambasted. His famous exchange with a Senator over whether or not a CRIME SUSPENSTORIES cover featuring a severed head was done in good taste (Gaines, admittedly lethargic from cold medicine, was backed into a corner and replied in a monotone that he thought it was in good taste, for a horror comic) was only the most publicly damning bit of coverage to come out of the hearings. Wertham was given a pass in the media, despite the fact that his book consisted largely of conjecture and opinion and that he misrepresented some of the comic stories he excoriated during the hearings.

Public sentiment turned against Gaines seemingly overnight as newspaper and television broadcast the “severed-head exchange” for all to see and hear. Gaines, and by proxy the comics industry, was seen as a group of amoral profiteers out to make a living at the expense of children’s welfare.

Gaines left the hearings in shock, knowing that he had done more damage than good. But still he fought to keep his comics free from censorship. While he was forced to cancel many of his comics due to their very titles containing now-banned words, he refused to join the newly created Comics Code Authority. But this stance was fatal to EC Comics — many distributors now refused to touch comics that didn’t carry the Code stamp of approval on their covers. Gaines persevered for a time despite constant haranguing by Code authorities, but EC published its last comic book in 1956.

Gaines tried other ventures, but none panned out. His one remaining bright spot was MAD magazine, which sold well throughout the hearings and beyond, and has outlived Gaines and is still being published in the 21st century.

In 2006 Gemstone Publishing undertook the monumental task of producing newly recolored, hardcover reprints of all the EC material, so new generations can see these trailblazing, creatively stunning stories in their full glory.

Up to Code

Following EC’s demise, publishers continued to adhere to the Comics Code with only a few notable exceptions. In 1971, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare approached Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief Stan Lee to produce a comic book about drug abuse. However, depictions of drug use of any kind were outlawed by the code. Lee published the comics (AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #s 96-98) without the code.

The advent of comic-book specialty stores in the 1980s decreased the industry’s dependency on newsstand distribution, which allowed for the advent of more code-free comics being offered from smaller publishers. Finally, in 2001, the code’s relevance reached its nadir, when Marvel Comics officially withdrew from the Comics Code Authority and instead instituted their own ratings system. Today, DC Comics’ children’s line and Archie Comics are the only publishers still submitting their comics for code approval.

Through it all, the comic-book industry itself managed to live up to the standards set by many of the heroes who appear on its four-color pages: every time it’s been knocked out and left for dead, it has managed to right itself and live to fight another day. And such was the case here. The advent of the code led publishers like National, with their wide range of uncontroversial superhero titles, to create more and more superhero comics that appealed to an ever-increasing range of readers.

The loss of EC Comics is not easily measured but is profoundly felt. While the larger industry survived and even prospered, one can only imagine what Gaines, Feldstein and their unparalleled stable of artists might have accomplished had they been allowed to continue their work.

Actually, Gaines did, briefly, try to work with the Code, but found it didn’t matter. The most famous example is the reprint of the story “Judgement Day,” in Incredible Science Fiction #33. The code demanded that an astronaut in the story be changed from a black man to white, which Al Feldstein pointed out was the point of the story. The Code refused to back down from their demands. Gaines threatened a lawsuit and refused to make changes, publishing the story anyway, but it was the final nail, leading to EC taking Mad, their only profitable book left, to magazine format and Code-free territory.